OTHER ANCIENT NEW ZEALAND CRANIUM TYPES.

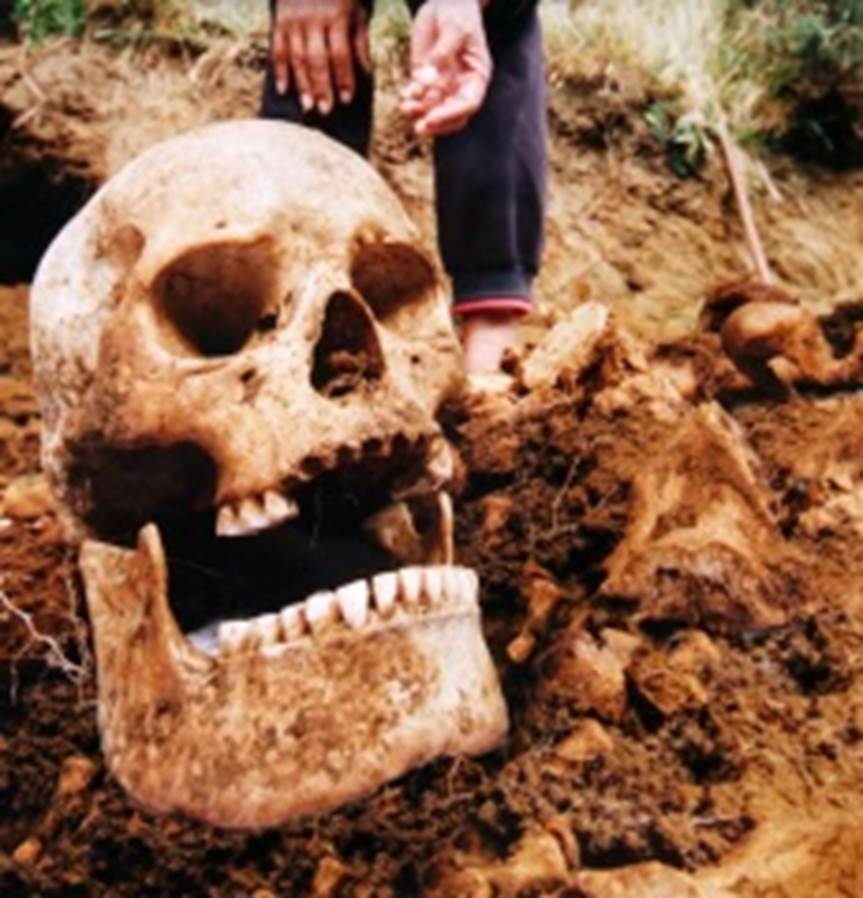

Here’s yet another non-Maori cranial-type which appears to be very ancient. The eye-sockets are strangely oval in shape.

This is undoubtedly the physical-type commented about by Trevor Hosking in his book, A Museum Underfoot ISBN 978-0-473-12308-6.

During the building of the Tokaanu race and power station at the extreme southern shores of Lake Taupo (1966) Trevor was informed of a skeleton find that he was called upon to investigate. He writes:

‘THE DISCOVERY OF A TOMO BURIAL

‘As project archaeologist I was constantly researching and recording sites throughout the scheme from Waiouru in the south to Tokaanu in the north and all points to the east and west. I was also on call to anywhere in the area should anything of interest turn up. This account covers just one of many incidents.

The phone rang while I was writing up my daily work book. Bones had turned up in a borrow pit near the tokaanu Stream just over the bridge on the left hand side, and off I went. An engineer was present, as well as a half loaded truck with its driver, a three yard bucket loader with engine running and a load of spoil but no sign of its driver. It was hardly surprising as the driver was Maori and there sitting on the top of his last bucket of spoil were three human skulls.’ …I never did find out if the scoop driver returned to the job.’

‘The priority was then to clear the tomo site of bones. Some eight feet of pumice had been removed before the bones were discovered. The skull shapes were quite different to those of modern humans and I was fortunate to have access to the late Lesley G Adkin who provided me with his research papers on the Horowhenua burials and the types of skulls found in that area.

Adkins information tied in exactly with what I had been turning up while working throughout the Turangi area. The loader driver had unearthed the skulls of a very early, pre-Polynesian people. These early skulls had a loaf shape when viewed from the rear. The skull widened from the bottom of the parietal – about the level of the top of the ears. It then curved in and up to a pronounced crestal ridge. From the front the jaw was broad and solid with a pronounced ridge above the eye socket, from which the skull sloped slightly backwards. The skull also had a very thick bone structure and is typical of an archaic people whose remains have been found alongside Moa bones. On the other hand more recent people have a more rounded skull when viewed from the rear, a little like a basket ball. The forehead is more vertical and there are no eyebrow ridges.’

Note: This description of basketball shaped skulls and no eyebrow ridge is uncharacteristic of the Polynesian skull (with its pointed vault and eyebrow ridge), but very characteristic of Lake Taupo vicinity, Ngati-Hotu skulls as in the “coffin” picture above. Trevor Hosking continues:

‘The controversy over the date of first settlement of New Zealand continued. Elsdon Best, a prolific author of New Zealand pre-history, calculated the date of arrival of the fleet based on stated generations given by Maori elders. He was well out because in the telling of whakapapa, only male births are remembered. Families with all female members were not accounted for. Consequently his 1350 date clashes with the C14 date for people who visited the cave at Whakamoenga Point, Taupo. I excavated and recorded the evidence that proved the people used the cave and ate Moa while there.’

THE TALL ONES

On the West Coast of the North Island, ranging from Waikato Heads to Mitimiti and beyond were people that achieved heights of 7-8 feet. Maori oral traditions speak of these people and their eventual annihilation. This photo of a giant skull was taken in the vicinity of Waikato Heads.

For a more comprehensive study of the wide diversity of “Maori” physical-types observed by early colonial anthropologists see , Physical and Mental Characteristics of the Maori, Volume 1, by Elsdon Best, 1924.

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Bes01Maor-t1-body-d1.html

NOW, BACK TO WAIRAU BAR.

THE ANCIENT LAPITA PEOPLE OF OCEANIA WHO PRE-DATED THE POLYNESIAN MAORI BY THOUSANDS OF YEARS

There were yet other peoples who ranged all over the Pacific Ocean long before there were any Polynesians. These much earlier inhabitants (1500 to 500 BC) were known as the Lapita People and their funerary practices, as well as grave goods placed with the deceased, show similarities to the burials at Wairau Bar.

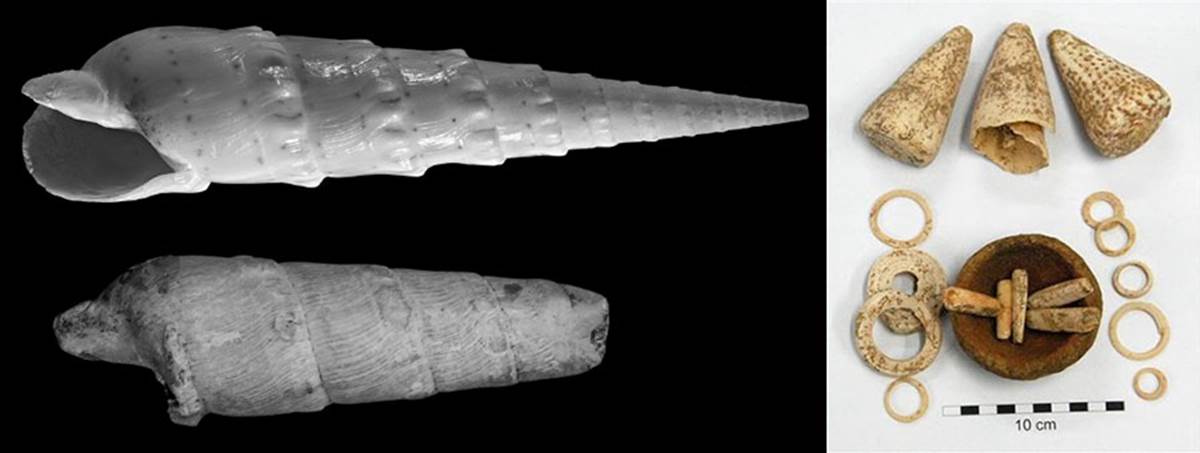

Inexplicably, a worked or carved shell (Acus Crenulatus) purportedly from the much warmer regions of East Polynesia, but said to be not indigenous to New Zealand or periodically washed up on New Zealand shores during storms (like some shells as far away as Mexico), was also found at Wairau Bar.

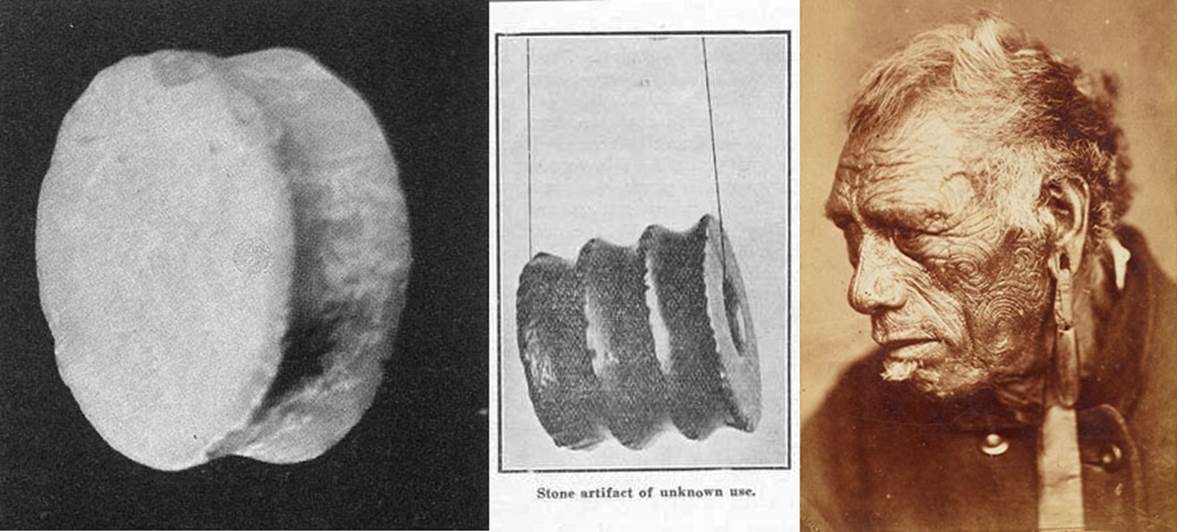

To the left are seen two examples of Acus Crenulatus shells, the bottom one of which was found in a grave at Wairau Bar. The species is not indigenous to the colder, sub-tropical waters of New Zealand.

To the right are seen a Lapita grave goods jewellery box from circa 1000 BC or before. Note the array of cut circular objects, including a small burial pot and ringlets.

The grave also contained shell bracelets and the Lapita artisans were slicing large shells into sections for this purpose. Objects seen within the jewellery box are pendants with holes drilled through them. Such beautifully fashioned ringlets served as conus-shell currency in many ancient societies, ranging from Angola to the Sudan in Africa, to the Americas and all the way across Oceania to New Guinea. The giant stone money discs of Yap Island in the Caroline group of Micronesia were in the ancient Lapita sphere of cultural influence and the ancient tradition of making the huge discs, or the Nan Madol stone city at Pohnpei, undoubtedly stems from the Lapita-era of habitation.

In the article, Connections With Hawaiiki: the Evidence or a Shell Tool from Wairau Bar, Marlborough, New Zealand, by Janet Davidson, Amy Findlater, Roger Fife, Judith MacDonald and Bruce Marshall, Journal of Pacific Archaelogy-Vol. 2, No. 2, 2011, considerable effort is made to convince the reader that this solitary worked Acus Crenulatus shell proves that the Wairau Bar people came directly from East Polynesia, in 1250-1300 AD (700-years ago) bringing the shell with them. Dr Janet Davidson, however, was unwilling to nominate a Pacific Island source from which this particular shell species could have originated.

It almost smacks of desperation on the part of Davidson et al to base such a huge, far-reaching but singular conclusion on such a flimsy piece of very selective evidence, for the following reasons:

The primary or best known source of this shell species is the Red Sea region bordering Egypt , extending to the Indian Ocean bordering countries, the Maldives, Madagascar, the Mascarene Basin and Tanzania. The species is also found in the extreme Eastern Pacific Ocean on islands off Mexico.

The Red Sea region is the point of origin where this particular variation of the sharply-pointed, worm mollusc is considered to be indigenous or most prolific, so why didn’t Davidson et al advance an alternative migration theory relative to that theatre, half a world away from Polynesia?

The Maldives, especially, was world renown as the source of shell-money (mainly cowrie shells) used as a valuable item of exchange in the BC & AD epochs, from Egypt and Mesopotamia, extending as far North of the Persian Gulf as the Finnish-Urgic regions, the Caspian Sea and Northern Norway on the Arctic Circle. Some of the money shells from the Red Sea, found within Indus Valley graves, date to 1500 BC.

One group of the earliest known inhabitants or the Maldives Islands were the Redin or lion people, who occupied the Islands from, possibly, as early as 2000 BC until about 500 BC.

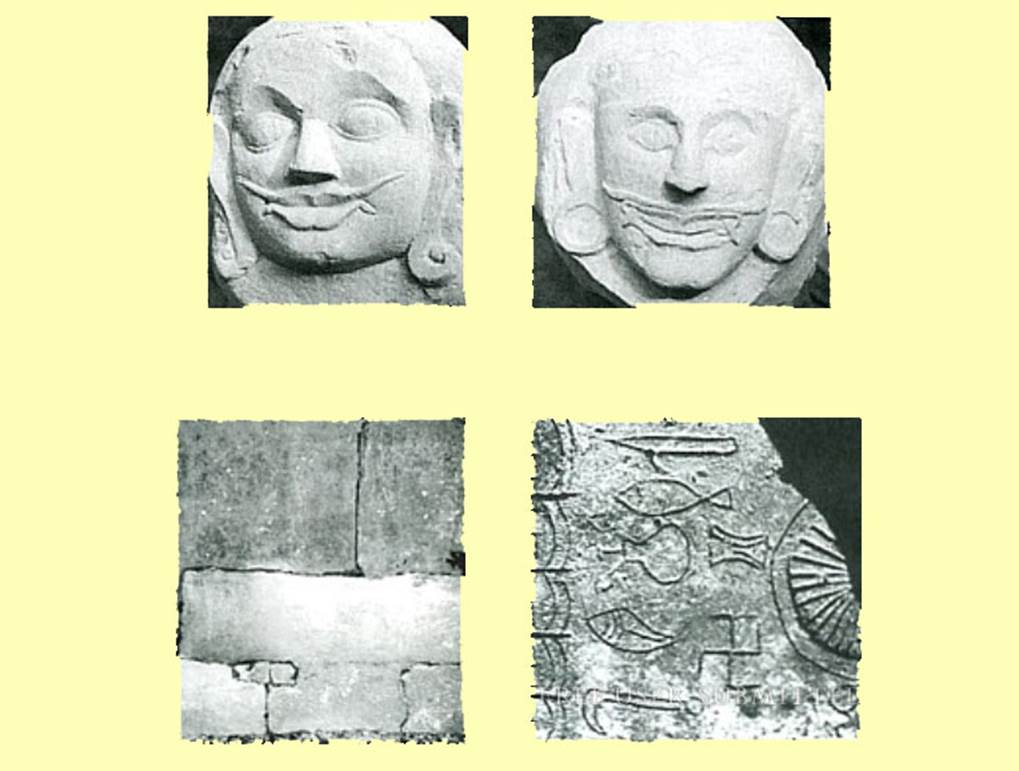

In Maldives oral tradition, they were described as people with red or blond hair and blue eyes or of Caucasoid-European physiology, just as their surviving busts and statuettes attest.

The ancient Redin civilisation of the Maldives wore moustaches (like the Lapita people) and used ear-disc weights to elongate their ear lobes, which hung almost to shoulder length in exactly the same way as displayed on the giant moai statues of Easter Island half a world away in the Pacific. They were also depicted as having lion’s fangs protruding from each side of the mouth. Their beautifully fashioned stone temples contained lion statuettes, although there were no lions in the Maldives. Motifs on walls depicted sun-wheels, swastika sun symbols and other designs consistent with early Indus Valley civilisations and sun worship.

The Redin of the Maldives were supplanted by an incoming Buddhist civilisation in about 500 BC and most of these seafaring folk chose to abandon the Maldives and seek other homelands elsewhere.

There were many choices available for destinations to the 4 quarters of the Earth and its secondary points, according to the monsoon method of sailing that would have been well known to this maritime civilisation living amidst their 1200 island’s group. One seasonal current could take them down the coast of Africa and into the Atlantic, carrying them to South America and the Gulf of Mexico.

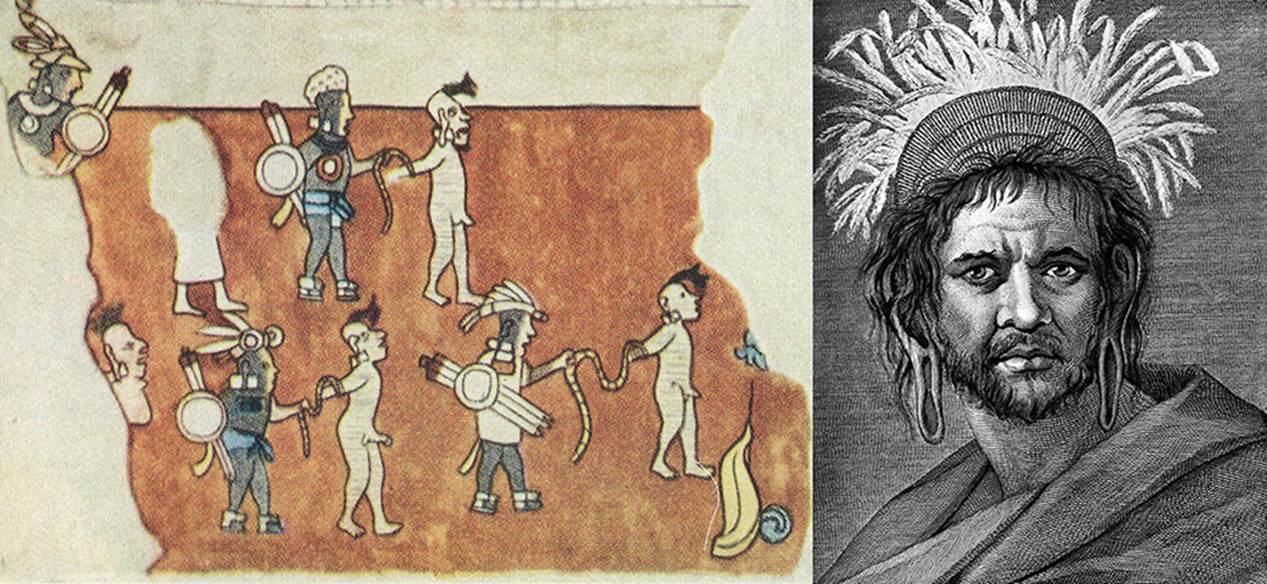

Murals at Chitzen Itza seem to tell us the final fate of the progeny of these long-eared people who chose that destination.

Left: The long-ears of the Yucatan Peninsula, defeated, stripped of their possessions and led into slavery or sacrifice upon the altars of their Mayan conquerors. See: Mural from the Temple of the Warriors, Chtizen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico.

Right: One of the few surviving “long-ears” found at Easter Island (Rapanui) when the first European exploration ships arrived.

Obviously a branch of the same long-ear civilisation managed to survive at Easter Island until more recent centuries, until decimated by the incoming Polynesians.

Left: From Mexico to Peru bearded human figures were depicted with earplugs adorning the earlobe holes. This practice was general amongst royalty especially. Right: one of the South American earplugs.

It’s certainly probable that escapees from Easter Island made it to New Zealand and Waitaha oral traditions seem to support that. However, if the practice of ear elongation carried on in New Zealand, how would we know? It was not practiced by the Polynesians, although, in New Zealand, long greenstone ear pendants were carved by the earlier inhabitants and the practice of wearing them was adopted by Maori as symbols of prestige and office. The long pendants seem to be in similitude to the ear lobes of the long-ears that extended to the shoulders.

Also, a variety of circular Moa bone or shell discs found at archaeological sites in New Zealand might suggest that they functioned as earplugs within enlarged ear-lobes. However, any such identification would be a most unwelcome find, vehemently discounted by our politically-correct and racially sensitive experts, with artefact evidence made to disappear from public view, like a variety of other anomalous items.

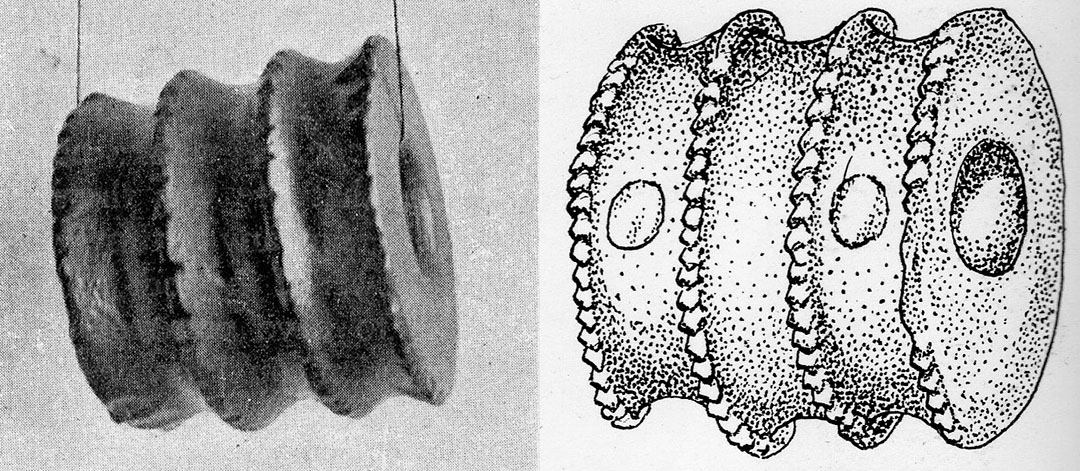

To the left is seen a ceramic earplug worn by the long-ears of South America. Centre is seen a stone artefact of unknown use found in New Zealand. Could this possibly be a long-ears plug with provision for additional cord suspension and support over the ear-top? Why was it laboriously carved from stone? Right: At least some earlobe elongation was practiced in New Zealand into the colonial era and the many long stone ear pendants seem reminiscent or in similitude of the dangling earlobes of the Easter Islanders or their South American predecessors.

The triple circle-grooved object to the left was found at Wairau Bar in New Zealand's South Island and is made of stone. The one on the right, is fashioned in shiny black argillite stone and was found at Oruarangi, Hauraki, Auckland district, North Island. Both are attributed to the early "Moa-Hunter" epoch of New Zealand and are called neck pendants, although Roger Duff has mistakenly given a width measurement for the reel on the right as 38 cm when it should read 38 mm. It's more likely, given the central reel cavity, that these served as ear plugs or ear-pendants for individuals carrying on the "long-ears" tradition, practiced from the Maldives to Mexico to Easter Island and onwards to New Zealand.

The author wearing an authentic Portuguese helmet that was dredged up from deep mud in the Manukau Harbour, Auckland, New Zealand in the late 1960s. It is now in a private collection but the full circumstances of the find are very well documented beyond dispute.

The owner of the helmet loaned it to Auckland Institute and Museum for about a decade, but inasmuch as it didn’t go on public display, and no historical significance was attributed to the find, the owner retrieved it. He noted the sarcasm of the museum functionary delivering it back into the his possession, inferring that he & his curator colleagues knew the true significance of the find but weren’t permitted to divulge that information to the public. The functionary stated, “we’ll say it came from Abel Tasman’s exploratory visit”, knowing full-well that was impossible, but the lie would be sufficient to keep the public in the dark. Amongst other things, the helmet has seen combat, as there’s a sword-strike dent in it.

And here’s what a helmet from Abel Tasman’s Dutch crew would have looked like:

A helmet from Tasman’s expedition would have had this shape.

Left: Yet another helmet was dredged up in Wellington Harbour and is attributed to the Spanish, although it’s not typically Spanish from the conquistador era. Right: A Tamil Bell with Muslim writing around its centre section was found in Northland New Zealand in about 1836 and dates to about the year 1400 AD.

With regards to the so-called Spanish helmet, our experts came up with a scenario, put before the public, that the helmet must’ve been a souvenir of an early colonial immigrant to New Zealand who had it balancing on the rail of the ship as it docked in Wellington Harbour, then the helmet fell it off into the sea … how clumsy can one be!

Likewise, the brass bell that came off a Tamil ship was not on display for years. A friend visiting Wellington enquired after its whereabouts and was told by a museum staff-member that it was not on display because there was insufficient public interest about the item … Yeah, right!.

SO, FROM WHICH DIRECTION DID THESE ITEMS COME?

A second migratory route for the early era Redin vacating the Maldives (circa 500 BC) could well have been via the South Equatorial Current to Australia and New Zealand, the same current that allowed the Tamil, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch and English to find New Zealand and Australia.

Portuguese conquerors had taken the Maldives and ruled there for 15-years between 1548 and 1573 until ousted in a bloody uprising by the Maldivians, where the hated Portuguese were put to the sword.

The Tamil civilisation occupied the south-eastern reaches of India down to its southern-most tip. Tamil Nadu was only about 340-miles distant NE from the Maldives.

Remnants of the much earlier Redin people continued to live in the Maldives through the many centuries and subsequent takeovers by new conquerors, sufficient for oral tradition descriptions of them to survive to the present day. Latter incoming groups to the Maldives, like the Buddhists and Hindus, even adopted the practice of ear elongation.

All-in-all the Maldives has been a hive of (mostly peaceful) activity, a trading-region and maritime thoroughfare for millennia, with wave after wave of foreign vessels stopping by from many scattered civilisations. Some pottery shards found there date from 2000 BC, with latter examples being of Buddhist, Hindu, Chinese, Tamil, Greek or Roman origin, etc.

Pliny the Elder wrote, in 79 BC, about Roman maritime visits to Sri Lanka (450-miles ENE) and any such ships would have passed through the Maldives. Not surprisingly, a Roman coin was found in a stupa (Buddhist shrine) in the Maldives. It was housed in a stone box within a central chamber. The coin had lain undisturbed within the archaeological site until the 20th Century and was identified as a Roman Republican denarius of Caius Vibius Pansa, minted in Rome in 90 BC … which raises yet another point about Wairau Bar, NZ evidence to be considered.

In 2010, Dr. Janet Davidson happened upon the well-worn Acus Crenulata tool in a half-forgotten collection of artefacts dating from a dig undertaken 70-years prior at Wairau Bar. She subsequently built a very imaginative hypothesis about the significance of the overlooked find.

Yet, if a scientific approach about evidence is adhered to, all other archaeological finds from the self-same region should be granted equal consideration. Despite this, a very significant discovery nearby gets no honourable mention.

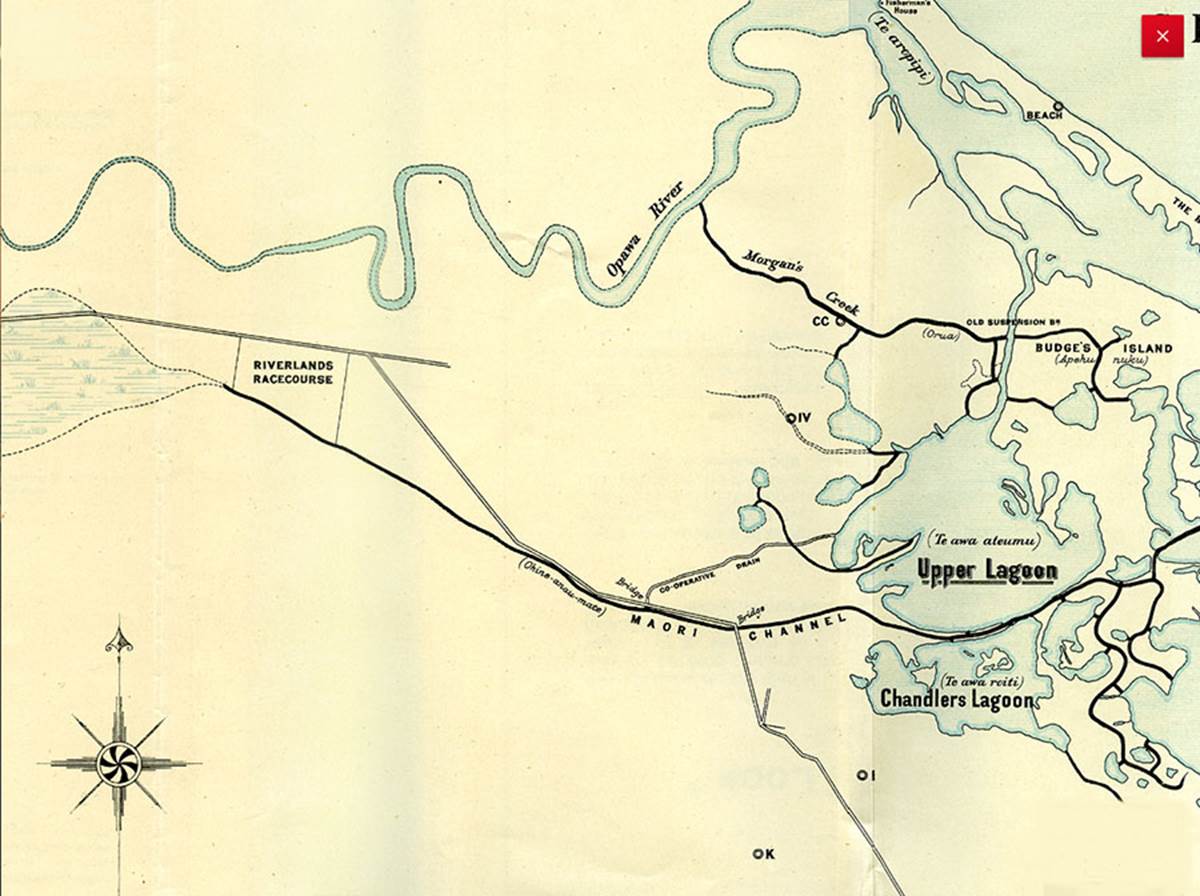

In December 2003 a Roman coin was found on the banks of Taylor-Reserve, a tributary of the Opawa River that flows into the sea a stone’s-throw from the archaeological site where the Acus Crenulata shell was dug up. The coin was within the same alluvial plain and canal system as the Wairau Bar seaward site and only 5-miles further distant up the same river that exits Wairau Bar.

It was brought to the surface by a long reach digger and had formerly lain in substrate soil well below the surface.

This Roman coin is dated 7 BC and was minted by Marcus Salvius Otho, grandfather of the Roman Emperor Otho. The head is the image of Caesar Augustus and the surrounding lettering is thought to read: CAESAR AVGVST PONT MAX TRIBVNIC POT

The opposite side reads: M SALVIVS OTHHO IIIVIR AAAFF

It was found by archaeologist Reg Nichol and is presently on display in the foyer of the Marlborough District Council in Blenheim, New Zealand. Yet another Roman coin was dug up by a Mr. Tasker of Hastings, NZ some years ago when he was digging a hole for a clothes line post on a new subdivision where no houses had been previously.

As it turns out quite a number of other Roman coins have been found in New Zealand since the dawn of the colonial era:

- On the 14th of November 1878 a coin from the era of Julius Caesar (who reigned from 46-44 BC) was located 2-feet below the surface of the ground at Mount Victoria on Auckland's North Shore. The find was reported in the Evening Post, as well as the Auckland Star, Thames Star and Hawkes Bay Herald in the days following.

- A Roman coin was found at Invercargill, South Island on or around the 6th of September 1894 and reported in the Otago Witness.

- A Roman denarius coin was dug up from clay subsoil at Ponsonby, Auckland around the 16th - 17th of September 1903 and reported in the New Zealand Herald on the 19th of September 1903. It was of the era of Constantine (who reigned from 306 to 337 AD). The coin went into the collection of the Auckland Museum.

- A reasonably short distance from where archaeologist, Reg Nichol found the 7 BC Roman coin in 2003, yet another one was found at Picton, as reported in the Evening Post, 22nd of December 1917. This one had been struck during the reign of Constantinus I and was dated to about 292 AD.

- Another Roman coin was discovered on the foreshore of the Manukau Harbour in 1931 and reported in the New Zealand Herald on the 7th of February 1931.

- A Roman coin bearing the image of a clean shaven man wearing a laurel wreath was assessed by the Dominion Museum numismatist in 1935 and thought to be 2000-years old. It was bronze and covered in a dark green verdigris, indicating great age. It seems to have been found in the Wellington region and a report concerning it appeared in the Press, 16th of July 1935.

Of course, in a cultural-Marxist atmosphere, where history has to support the views and agendas of the political organs there is no way it could be entertained that any of these coins arrived on New Zealand shores in antiquity or contemporaneously to the very labour-intensive canal-building excavations going on at Wairau Bar … unthinkable! … preposterous!

The simplistic and unrealistic view concerning all of these coins is that they were dropped by clumsy colonial settlers, walking around with holes in their pockets. A New Zealand Herald journalist found this trite explanation unconvincing when writing an article concerning the Ponsonby find of 1903:

'It is very strange to think that any one of our early settlers, our blue shirt or blue jumper pioneers, should be going about in Ponsonby with a Roman coin in his pocket, that he should drop it, and that afterwards, in the year of our Lord 1903, it should be dug up. The chances are, one would think, about about ten million to one against all these contingencies.'

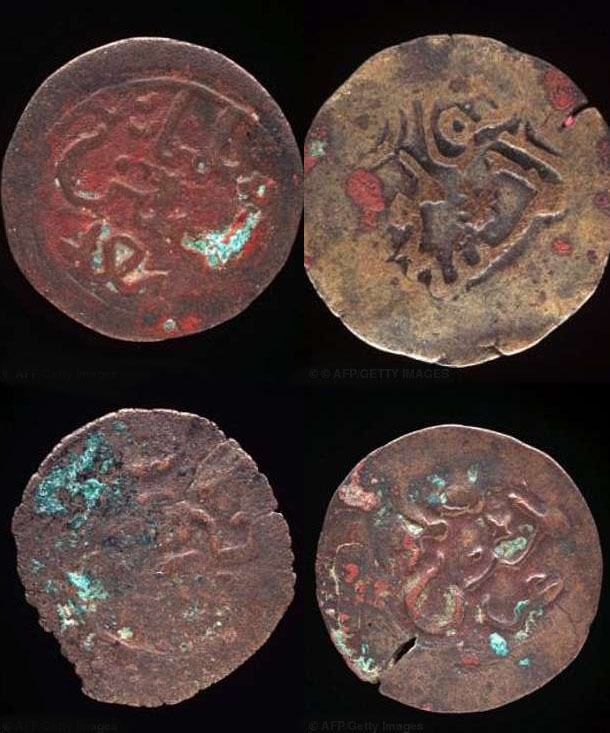

Oh, but here’s another one found in the Queensland bush of Australia, this time of Greek/Egyptian origin and dated to the era of Ptolemy IV (221-204 BC).:

This coin from Egypt, under Greek rule, was found by a farmer digging a post hole in a far north, Queensland, Australia rainforest. Ancient mariners coming through the Red Sea into the Indian Ocean could be drawn seasonally to Australia and New Zealand by the south equatorial currents that brought many latter explorers into the region.

A ship dismasted in the Indian Ocean and left to drift could easily end up on the Poutu Peninsula of New Zealand's West Coast, Northland or be dragged through Cook Strait between the North & South Islands to flounder on east coastal regions of either island.

Greek coins were circulating in abundance around Egypt by 300 BC and some Greek garrisons had been stationed there since about 650 BC. Full Greek annexation followed the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great (332 BC) and Roman conquest of the region occurred in 30 BC.

Whether or not any Roman or Greek ships, per say, were drawn by the natural southern equatorial currents to Australia or New Zealand is yet to be ascertained, but their coins certainly made the journey in the possession of early explorers issuing forth from the Mediterranean and Red Sea regions.

INDIAN OCEAN COINS, OF A TYPE UNIQUE TO KILWA AFRICA & THE ARABIAN PENINSULA, FOUND IN AUSTRALIA.

In 1944, Royal Australian Airforce Radar operator, Maurie Isenberg, found 5 African Kilwa coins at the Wessel Islands, Australia. Yet another one was found by archaeologist, Mike Hermes in the same location in 2018. The coins could be 1000-years old.

The only other locations where this type of coin has been found is at Kilwa Island, off Tanzania or the Arabian Peninsula. Historically, Kilwa was the center of the Kilwa Sultanate, a medieval sultanate whose authority at its height in the 13th-15th centuries CE stretched the entire length of the Swahili Coast. The Portuguese raided Kilwa in 1505 and archaeologist, Mike Hermes, speculates that they ranged far beyond their possessions in the Indian Ocean, using the seasonal monsoon currents and winds (monsoon sailing) to find Australia ... & brought some Kilwa ill-gotten-gains booty with them.

THE PRE-POLYNESIAN LAPITA PEOPLE WHO RANGED FAR AND WIDE ACROSS THE PACIFIC

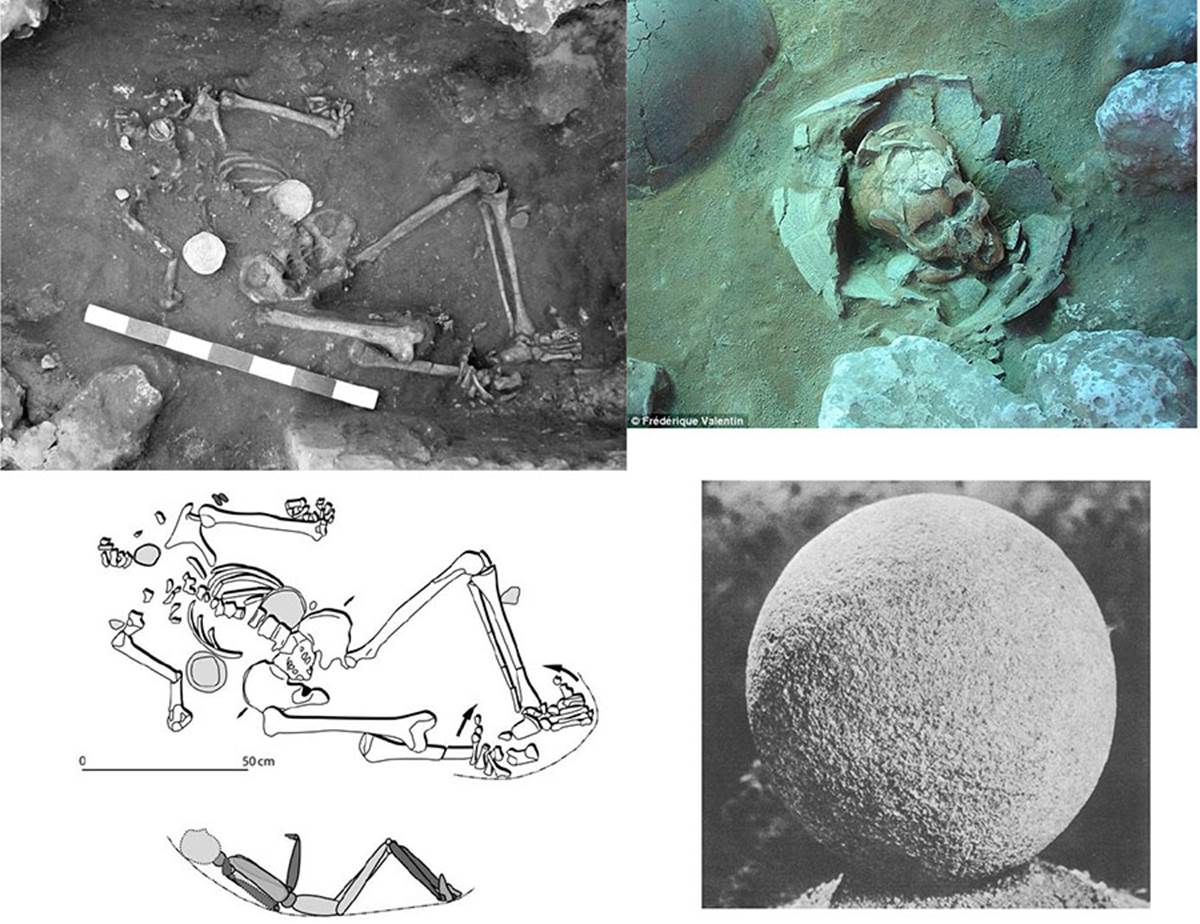

Adze tools, often finely fashioned, along with ornate necklaces and very round burial pots (reminiscent of the Moa eggs and all the other circular paraphilia in Moa Hunter graves of New Zealand) were very much a part of Lapita People burials for circa 1500 BC to 500 BC.

To the left is seen a Lapita People skeleton exhumed at Teouma, Vanuatu. The head is missing, which is often the case in both Lapita and Wairau Bar (Moa Hunter) burials, with the heads frequently deposited elsewhere. Circular, unworked Geloina shells are seen to have been placed on each side of the body.

Top right: A head was separated from the rest of the skeleton and placed within one of the very circular and ornate Lapita burial pots. The Wessex People of ancient Britain (2500 BC to 800 BC) also buried their dead accompanied by ornate burial pots that carried quite similar design features of chevrons, lozenge and knop-dots.

Like the North American mound builders who carved shells into ornate shapes and placed them into graves, the Wessex People burials have also been known to contain shell treasures and also chalk balls.

Bottom right: In ancient Costa Rica carved stone balls were often placed in graves (BC era) for the journey of the afterlife, again reminiscent of the Moa eggs found in many Moa Hunter epoch graves. An ancient burial at Pigeon Mountain, Pakuranga, Auckland, NZ was, similarly, reported to have a ball (pumice) included.

DID MAORI HAVE ORAL TRADITIONS ABOUT HUNTING THE GREAT MOA BIRD?

When early colonial era Europeans came to New Zealand, and more especially the South Island, it wasn’t too long before they came across bones of birds that had been of immense size. More complete skeletons of the birds could sometimes be found in limestone tomo holes, where the giant birds had fallen in and perished.

Knowledge of the now extinct species reached the attention of CMS Mission printer, William Colenso, who arrived in the country in 1835 to work at the Bay of Islands. He apparently gained no knowledge of the former existence of Moa birds until after 1838, when his interest was piqued and stimulated to find out more about the fascinating species. In his much-respected position as CMS Mission printer he had considerable access to learned Maori individuals and had no hesitation in asking them about the giant birds. Here, following, are excerpts from the book: The Moa Hunters of New Zealand – Sportsman of the Stone Age, by TL Buick, 1937.

“… after vain inquiries and many disappointments he (Colenso) was able to acquire a few bones but not a great deal of information regarding this denizen of the mountain-side. What most impressed Colenso in these investigations was the apparent absence among the Maori people of any settled traditions concerning the bird. To him it seemed incomprehensible that a bird so remarkable in size and character should have escaped the notice or failed to excite the wonder of a people meticulously shrewd in their habits of observation and traditional record. To Mr. Colenso the logic of such a situation was that if the Maori had not preserved the Moa in tradition, that could be only because the Maori had never been in contact with the bird and knew nothing of it.”

In an article written for The Tasmanian Journal of Science in 1842 Colenso thus states the position as it appeared to him:

“From Native tradition we gain nothing to aid us in our inquiries after the probable age in which this animal lived; for although the New Zealander abounds in traditionary lore, both natural and supernatural, he appears to be totally ignorant of anything concerning the Moa save the fabulous stories already referred to. If such an animal ever existed within the time of the present race of New Zealanders, surely to a people possessing no quadrupeds, and but very scantily supplied with both animal and vegetable food, the chase and capture of such a creature would not only be a grand achievement, but one also, from its importance, not likely ever to be forgotten, seeing, too, that many things of minor importance are by them handed down from father to son in continued succession from the very night of history. Even fishes, birds, and plants anciently sought after with avidity as articles of food, although having never been seen by either the passing or rising generation of aborigines, are, notwithstanding, both in habit and uses, well known to them from the descriptive accounts repeatedly recited in their hearing by the old men of the village.”

Taking, then, the paucity of tradition as he supposed it, together with such other facts as he found them, Mr. Colenso came to the conclusion that:

“The period of time, then, in which I venture to conceive it most probable the Moa ceased to exist was certainly either antecedent or coetaneous to the peopling of these islands by the present race of New Zealanders.”

“Sir Julius von Haast was greatly influenced by Mr. Colenso's opinion, he admits; and he, too, became the doughty champion of the theory of the ancient extinction of the Moa, and at one time used the supposed absence of Native tradition as the sheet-anchor of his case.”

Later, WBD Mantell discovered former fire pits containing cooked Moa bones, obsidian flint knives and visible proof that Moa and their eggs had been placed in the cooking fires by “some branch of the human family.”

From the very best evidence that these early researchers could gather, Colenso, Von Haast, as well as a host of other scientific investigators, concluded that the Polynesian Maori had no oral traditions that would lead one to believe they had ever encountered, let alone hunted, the giant Moa bird. From this, the concept of the pre-Maori Moa Hunter came into being and was accepted as fact until more modern times, when political-correctness and racial-sensitivity issues began to fudge archaeological findings and dominate the interpretation of regional history.

Final acceptance of the fact that the Moa Hunter people occupied New Zealand at least 2600-years before the 1300AD coming of the Polynesian Maori was confirmed in the Poukawa archaeological digs of the 1960s. Under the undisturbed tephra ash-band layer of the 1320 BC Waimihia volcanic explosion, Russell Price and his teams discovered cooked, broken-up Moa bones, complete with obsidian-blade cut marks, where the cooked flesh had been cut-away and the bone marrow sucked out. These bones, as well as human made or modified artefacts, had lain undisturbed under volcanic ash since before 1350 BC.

THE WAIRAU BAR ADZE PROBLEM

Dr. Janet Davidson et al had a major problem to contend with and juggle. How do we drag the Wairau Bar find convincingly into the Maori epoch of circa 1300 AD and, against all the evidence to the contrary, convince the New Zealand public that these people were, in fact, Polynesian Maori and the first-ever inhabitants?

So, according to the fanciful, but non-credible story proffered by these social-engineers, a small group of individuals from Eastern Polynesia, probably due to a drift mishap, landed at Wairau Bar in 1250 AD and set up shop. From this meagre few, composed of say 6-7 individuals including both men & women, the community grew to be a few hundred individuals by about 1350 AD, by which time they’d pretty-much wiped out all the Moa bird species across the length & breadth of an entire country larger than Great Britain.

But somehow in that 100-year period, these intrepid explorer-hunters had found and identified greenstone 180-miles away SW, as the crow flies, through some of the roughest and most mountainous, impassable terrain in New Zealand. Not only that, they brought it back to Wairau Bar and, with no prior experience in carving greenstone, fashioned the incredibly hard stone with precision and to tolerances that had taken the Celts, Chinese, Olmecs and others centuries to master. One greenstone artefact recovered from a first-arrivals grave at Wairau Bar was a beautifully fashioned object in the shape of a whale’s tooth and there were also two greenstone adze heads.

But also included in the grave goods was an adze from Tahanga Hill, Opito Bay, Coromandel Peninsula, about 350-miles NNE as the crow flies. So, we’re expected to believe that these few-in-number, intrepid explorers negotiated their way overland or by sea to this overgrown and hidden hill, upon which no human had ever set foot. They then immediately recognised it was composed of high quality basalt hardstone so carved an adze and then included that in the graves containing Moa bone necklaces and eggs. Not only that, the Tahanga Hill stone was so good that the Wairau Bar seeding-population set up the equivalent of an adze factory and churned out adzes in vast numbers, which were then distributed and traded all over ancient New Zealand.

OPITO BAY, COROMANDEL PENINSULA, MOA-HUNTER COMMUNITY CONTEMPORANEOUS WITH WAIRAU BAR.

Adze blanks from Tahanga Hill, Opito Bay Coromandel. Beyond this rudimentary roughing-out stage, they were finely shaped up on the hill, then finished and polished in the sand dunes by the sea edge. These adzes, in differing styles, were produced in high numbers for many years and found their way to New Zealand’s most ancient sites.

An adze from Tahanga Hill, Opito Bay, Coromandel, New Zealand.

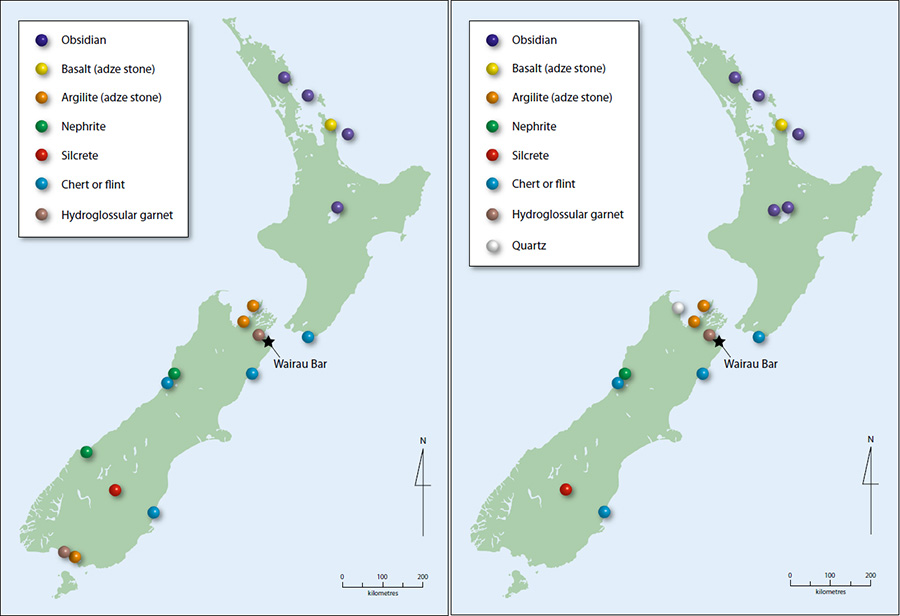

To the left is seen dots representing sources of specialised stone known to have been used as tools, etc, all across New Zealand in the first half of the 14th century AD (1300s). These stone resources were carried within exchange networks over hundreds of kilometres and up to 2000 kilometres from their source. To the right is seen originating locations of specialised stone that came in as trade goods to the Wairau Bar community.

https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/globalmigration/files/2018/09/Walter-et-al-2017.pdf

THE MOA HUNTER CANAL BUILDERS OF THE NORTH AND SOUTH ISLANDS OF NEW ZEALAND.

In 1903 CW Adams surveyed Wairau Bar and noted the existence of 12-miles (19 kilometres) of hand-dug canals. These linked the waterways of the alluvial plain together, bringing abundant fish resources into the region, as well as enhancing gardening. Extensive canal building and intensive wetlands gardening went hand-in-hand in other parts of ancient New Zealand as well.

This is only a part of a huge system of cut drains for eel traps and fertile, raised-earth gardening platforms sitting adjacent to the Awanui River, Northland. It was photographed by the US Airforce in 1944 and even by that time was in a severe state of decay due to abandonment and no maintenance for, probably, centuries.

THE NORTH DARGAVILLE CANAL BUILDERS, COUNTERPARTS TO THE WAIRAU BAR CANAL BUILDERS.

In a 1928 edition of the Journal of the Polynesian Society, Edwin Harding wrote of his family’s long-standing association with yet another district on the West Coast, where a huge complex of similarly abandoned drains were found. He recalled his early shepherding activities in a belt of coast, extending over 25-miles, between Maunganui Bluff and down beyond Dargaville.

Harding wrote, '...almost every hollow which had once been a lake or swamp had been similarly drained, noteworthy features being that the drains were perfectly straight and cut to the most direct outlet, involving in some cases, cuttings over twenty feet deep. The largest work is, I think, over a mile in length straight as a dart...a good many of the drains have now been obliterated by gum digging, cultivation or drifting sand, but some of the more striking works remain' (vol. 37, no. 4, pgs.367-368, Dec. 1928).

It goes without saying that the digging of large canal systems or the raised platform drainage systems for intensive gardening was a huge undertaking to create and maintain. There would have to have been a very sizable population to undertake this ancient work or even need such oversized systems.

But the overly-simplistic, unrealistic hypothesis of our experts goes something like this:

About 7 people find New Zealand in a drift mishap in say 1250 AD... about 5-minutes later they discover greenstone at Hokitika and know how to carve it ... 5-minutes after that they find high quality basalt rock at Opito Bay and start churning out adzes in vast quantity for national distribution ... about 5-minutes after that they've bred up such a sizable population as to have decimated all the species of Moa birds throughout New Zealand, have built thousands of huge PA fortresses, canal systems and intensive alluvial plain drain networks of raised garden systems, etc., ... Wow! ... that's fast-tracking!