BES OF EGYPT & TARANAICH-THOR OF EUROPE IN THE ANCIENT SOUTH PACIFIC.

Maori oral traditions clearly state that, upon arrival in New Zealand, Maori found that there was a large, well-established population already living in the country. The inhabitants were described as having skin complexion that was white to light-ruddy, with eye colours from blue to green to darker tints. Their hair colours ranged from white and dull-golden, with red being predominant in the general population. There were also shades of brown through to black and braided samples of this multi-coloured hair (taken from the Waitakere rock shelters) used to be on display at Auckland War Memorial Museum.

In physical stature most groups were about the same height as Maori, but there

was one widely dispersed group described as being considerably smaller (white

pygmies) with fine, childlike features, white-golden hair and large watery blue-green

eyes. Around Port Waikato and distributed up the West Coast beyond the Hokianga

Harbour to Mitimiti was yet another group who were very tall, achieving an average

adult height of around 7-feet. Since early colonial times the skeletal remains

of these people have been continuously observed as trussed, sitting position

burials in coastal sand dunes or laid-out horizontally in caves.

Maori used umbrella terms like Patu-paiarehe, Turehu

and Pakepakeha as names for these earlier inhabitants,

but each Maori tribe developed their own regional names, such as Ngati

Kura, Ngati Korakorako and Ngati

Turehu for the Patu-paiarehe tribes in the Rotorua lakes district

of the central North Island. The last, intact surviving tribe was the Ngati

Hotu who lived in Hawkes Bay district and later around Lake Taupo, until their

defeat in the Battle of the Five Forts.

The Maori term, Pakeha, later used to describe white

colonial Europeans, was derived from the ancient name Pakepakeha

used to describe the former white population. Pocket groups of these first inhabitants

survived into the 20th century and are well-remembered by old-timers as the

red headed, freckle-faced Maoris or waka blonds

New Zealanders will immediately recognise the stylised facial features shown on this belt buckle from Sutton Hoo in England as very similar to what's seen in Maori carving. A Scandinavian burial ship was also excavated on the same English site. On the above artefact a "high hat" is depicted above the "Tiki-type" face. The high hat or extended forehead representations of the "Tiki" figurines is very prevalent in Oceania or Egypt, but somewhat less common in New Zealand.

Maori oral traditions tell us that the Patu-paiarehe or Turehu people taught Maori many arts and crafts. These included fishnet making, weaving, haka (dance), the tattooing arts (moko), stick games, string puzzle games, putorino flute playing, carving, etc. At a later, hostile era the Maori warriors attacked these people, then enslaved and cannibalised them into virtual extinction. During this unfortunate period many Patu-paiarehe fled to the inhospitable and rugged high country for survival and later became known as “The Children of the Mist”. Around the Auckland Isthmus they subsisted in the Coromandel, Hunua and Waitakere high country forests. They hid in massive cave systems around Port Waikato and lived for many generations on Pirongia Mountain. In the northern regions they lived in the vast Waipoua Forest, the Waima Range or the rugged country around Pangaru and the Maungataniwha Range. Further South they were in the Urewera Ranges, at Mount Ngongataha in the central volcanic zone or, later, to the southwest of Lake Taupo in the vast rugged badlands around Atene above the Wanganui River. In the South Island they were living in the hills around Lyttelton Harbour, Akaroa and the Takitimu range as well as in hill country between the Arahura River and Lake Brunner, etc.

Entire villages, totems, canoes, greenstone treasures, musical instruments, ornately carved feather boxes and all possessions of the earlier people fell into the hands of the Maori conquerors as the spoils or prizes of war (muru-plunder). Patu-paiarehe arts, crafts, or all treasures not hidden in swamps or buried for later retrieval, thereafter, became the objects associated with Maori culture and symbolism. However, the true pedigree of these ancient cultural or religious expressions extend back to the countries from whence the distant ancestors of the Patu-paiarehe came.

It appears obvious that some ancient groups came to New Zealand directly from early-epoch Continental Europe, evidenced by the kinds of astronomical and domestic use stone structures found on the New Zealand landscape (including many beehive house hovel dome villages, now reduced to stone heaps). Others came more directly from former European homelands at the eastern base of the Mediterranean, passing through Central and South America and Easter Island en-route and bringing a lot of flora with them from that region. Because ancient Europeans shared much of the same heritage, expressed through common measurement standards, religious beliefs, cultural idiosyncrasies, writing, incising, motifs and symbolism, language, plinn rhythms, dance, musical instruments, astronomical/ navigational sciences, etc., many cultural items tend to blend and blur into one related expression over several continents.

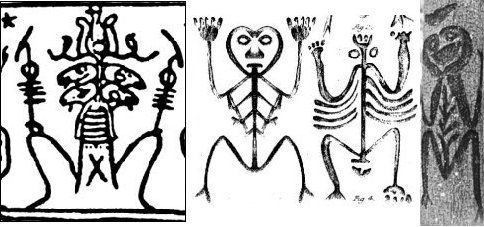

The strong cultural-religious beliefs, which led to the creation of carved

greenstone Hei-Tiki ornaments or pendants of Maori culture

and, more generally, worn by women, are traceable to Europe and the Mediterranean,

with their, pantheon of shared gods. Recognisable forms of the Hei-Tiki are

also found in Peru, Mexico, Palestine, and Southern Egypt. The New Zealand Hei-Tiki

pendant and the squat wooden or stone totems showing the same design attributes,

are a local version of Bes, the Southern Egyptian god of pregnant women mothers,

children and the home. When ancient Caucasoid tribes abandoned Egypt and its

satellite counties to the encroaching desert and migrated into the verdant territories

of Europe or elsewhere, they took their religious and cultural concepts with

them. Bes and his slightly variable counterparts in many lands was a much loved,

hairy and ugly, little bowlegged protector-entertainer god, found in statuettes

or murals scattered from Egypt to New Zealand...Bes/ Pan/ Puck/

Tiki/ Rongo.

He was Puca in Old English, Puki

in Old Norse, Puke in Swedish, Puge

in Danish, Puks in Low German, Pukis

in Latvian and Lithuanian. The pre-Christian Greeks represented him as a pipe

playing, fun loving, mischievous little dwarf-sator god, associated with fertility.

Whether Pan of Greece or Puck of Britain (also known as Robin Goodfellow),

he retained many attributes of the dwarf god Bes from Egypt. In Egypt he protected

mothers and children from snakes, scorpions and lions and was often depicted

as holding a snake in his left hand and a short sword cleaver in his raised

right hand. Some European portrayals of Puck show the snake in the left hand.

Much later the Roman Christians denounced the all-too-popular little Greek sator-shepherd

god and represented him as the devil (Satan), thus destroying

the adoration and high esteem formerly vested in him by the common people.

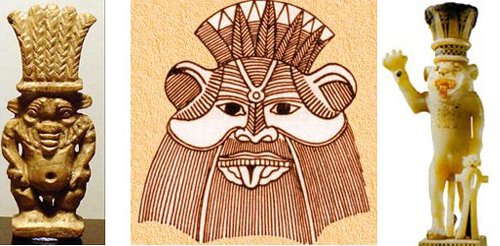

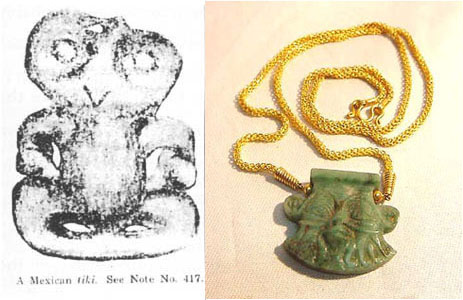

The ugly, but beloved little dwarf god, Bes of Southern Egypt, protector of pregnant women, mothers and children. He is shown here in typical stance, with his very pronounced "V" brow or forehead, which became the "V" forehead depression in the Tiki pendant. Generally, he would be shown with hands on hips or upper thighs and bandy legged, which became the adjoined arms and leg features on the Tiki pendant. He was often depicted as having big round "google" eyes, another attribute of the Tiki design. Bes was "hairy", with the hair ends of his beard curling into the (koru) spiral. Regionally, the greenstone or whalebone Hei-Tiki pendant was a development from the more commonly carved, New Zealand wooden totem, which stood adjacent to doorways or at gateway portals, where anyone entering had to walk past "Bes" or between his legs. These statue depiction's of New Zealand showed the tattooed "V" forehead (moko), the cheek spirals, based upon the beard hair spirals of Bes, the big head with the menacing expression, the protruding tongue (as shown above), The small body with the protruding and rounded tummy, a pronounced belly button and conspicuously exposed genitalia, arms and hands arching inward to the hips, upper thighs or belly, as well as bandy little legs in an almost squatting stance. The last picture in the above set, bottom far right, shows a column relief of Bes dancing for the children. Bes was very similar to the ungainly toddlers he was charged to watch over

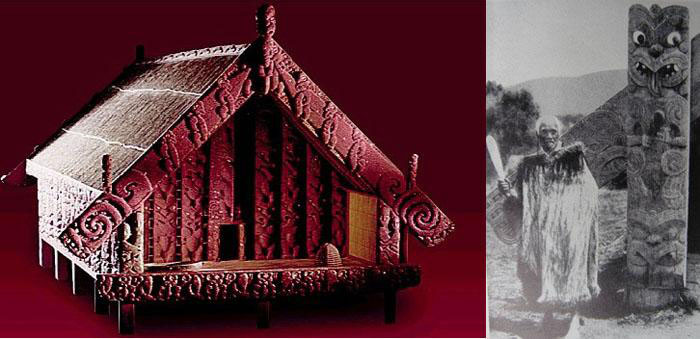

The ugly little dwarf god of Maori culture, tongue protruding and looking menacing, showing all of the same attributes as his Egyptian counterpart several continents and oceans removed, guarding the portals of this ornate Patu-pai-arehe/ Maori pataka building. Right: A Maori warrior with bulged out eyes, protruding tongue and a quivering-threatening mere weapon in hand, impersonates the menacing dwarf, depicted on the totem to the side. This carved figure was the sentinel at the gateways to villages, often brandishing his "SA" hieroglyph - Patu/ Mere-club, the sign of protection to the women and children of the village.

In Egypt Bes was fun-loving and danced for the children to make them laugh, but could turn terribly ferocious in their protection if they were threatened. As an ever-watchful guardian, he would spring like a dog at the throats of the ill-intentioned intruder. Bes was very much a part of family interaction in ancient Egypt, as elsewhere, and was a household deity. In some Mediterranean portrayals of Bes he plays a harp, tambourine or flute. His counterpart in Greece, Pan, played the pipes. A relief in the tomb of Hatshepsut illustrates Bes being present at her birth. Bes relief’s on Egyptian walls and birth houses suggest he was connected with childbirth and in ancient Egyptian tradition, when a baby smiled or laughed for no apparent reason, it was because Bes had pulled a funny face. He was always there in times of illness, childbirth or distress to comfort, help and protect.

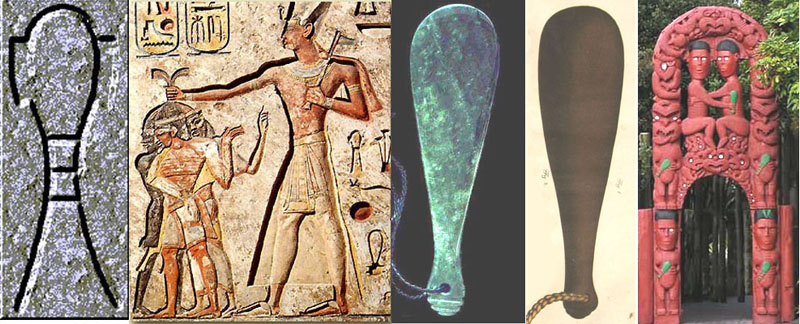

Bes, although of very genial temperament, was often depicted as carrying a weapon and in early Egyptian pictures or statuettes the weapon is symbolised by the hieroglyph SA, which is shaped quite like a Maori patu or mere club. The SA hieroglyph literally means protection. In latter Mediterranean depictions the weapon is a knife or short sword/ cleaver, which developed from the Egyptian Ankh symbol (a later development of SA), also used to signify protection. It is in direct consequence to this that totem statues at the entryways to Maori villages held a patu/ mere shaped club of the exact general design as those found in Egypt and Peru. The club itself symbolises the Egyptian hieroglyph SA-protection.

These totem statues warned the ill-intentioned, malevolent intruder, either

from the physical or spiritual realms, that the ever-vigilant dwarf was poised

ready to strike down any who came to do harm to the family.

Left: The “SA” hieroglyph. Next:

A relief showing Ramassees II dispensing of his enemies. To his side

is seen the SA hieroglyph, below which sits a glyph shaped like a patu club.

Next: A typical Maori patu or mere. Next:

A Peruvian club that is exactly the same design as a Maori patu, even duplicating

the stepped crossing lines adjacent to the wrist-cord hole (See: Antigüedades

Peruanas (Peruvian Antiquities) 1850, pg. 212, wherein the authors

state: ‘It is worthy of note that among the clubs there was

one, the form of which is completely identical with that which is used by the

inhabitants of New Zealand and other islands of the Pacific’.

Far Right: Maori palisaded villages or PA fortresses had carved

entrance gates depicting the ferocious little sentinel, ever-vigilant, with

his patu club at the ready. The same figure or figures are found on doorway

portals of community meeting houses, food-storage patakas or domestic dwellings.

As in ancient Egypt, these New Zealand figurines showed all of

the general attributes of Bes of Egypt.

The women and children of ancient New Zealand villages could live in confidence

that they would always be protected by the dwarf, whose vicarious representatives

on Earth were the men-folk or warriors of the village. Their inescapable duty

and responsibility was act fearlessly in the role of Bes/Rongo.

The New Zealand greenstone (jade) patu clubs were, originally, only for ceremonial usage, as the labour in carving and finishing such a precious, venerated, hardstone object could take the lifetime of a single artisan. Caches of greenstone objects have often been found in swamps, where the fleeing Patu-paiarehe hid them for safekeeping. Wooden or whalebone clubs were commonly used by Maori as actual weapons.

The fact that the New Zealand totems often depict the patu or mere club, which is so similar to the earliest SA hieroglyph representation, shows that the culture which originally, brought Bes-related religion to the country, instituted the oldest expressions.

One could confidently surmise that if a typical Maori statuette or totem of

the dwarf was placed into an Egyptian marketplace, many passers-by would immediately

recognise it as a depiction of the dwarf god Bes.

In Tahiti, Hawaii and other regions of Polynesia the Bes statue representations tended to retain the high hat of Bes, as seen in these Egyptian depiction's. Priests of those regions continued to wear the high hats as a symbol of office. The figurine to the left will be very recognisable to New Zealanders, as displaying the earliest form of "Hei-Tiki" attributes. All three pictures show the poking tongue, which is prominently displayed on early New Zealand wooden totems or stone effigies of the bandy-legged little god. In the right hand picture Bes is accompanied by the "SA" hieroglyph indicating "protection".

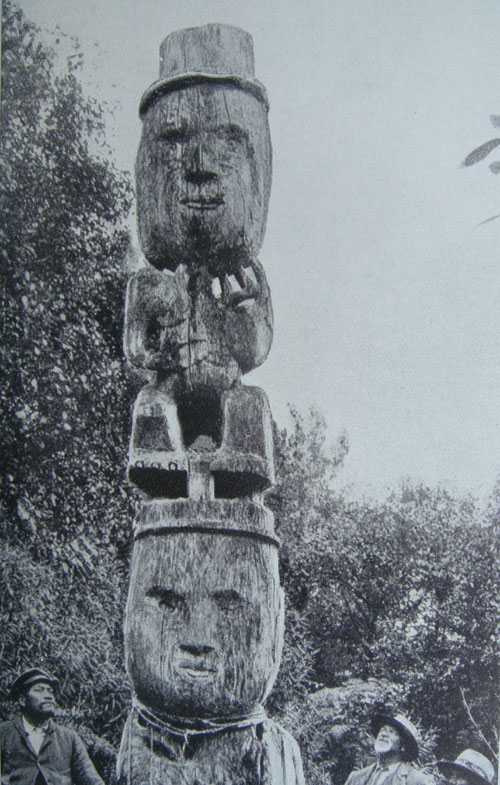

The figure on this very ancient wooden totem that once stood at Te Koutu PA, Lake Okataina near Rotorua, wears one of the flat hat-types associated with many Bes figurines of Egypt. The location was renowned for the ancient “Fairy People”, who dwelt throughout the region, until vanquished by the Maori warriors. At this hillock peninsula village on the lakeside, the ancient people lived in expertly carved-out subterranean dwellings, in a similar manner as in ancient Irish defensive enclosures. The hillock village is a labyrinth of these souterrain houses, numbering perhaps one hundred or more. All around the picturesque lake there are many hundreds of similar cliff or embankment-face homes, as well as communal caves with hand hewn tunnels branching off.

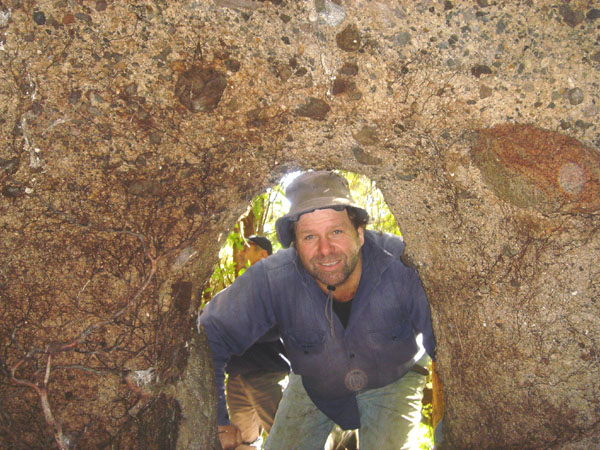

The cut recess to fit a door into one of the souterrain houses at Lake Okataina. The excavated dwellings were hewn into fairly hard material, but would have afforded warmth out of the wind, rain and misty-cold conditions of the high plateau lake, where the ancient Patu-paiarehe fled for protection from the marauding warriors. At the cluster of lakes in the vicinity they foraged for birds, eels, as well as freshwater kura (shrimp) and mussel shellfish. The deep forests around the lakesides offered some seclusion and protection from the cannibals.

Allan Titford entering through the doorway into a dwelling. Note the stone and hard aggregate in the wall and ceiling material. These lakeside apartments were carved out with considerable effort.

Yet another carefully carved interior with a gable ceiling. This one had alcoves in the side walls for comfortable, recessed seating, but for small people. Many of the dwellings or tunnels around the lake appeared to be purpose designed for the smaller stature Turehu people (white pygmy) who achieved a height of only 4 feet (1.2 metres). They had golden blond hair and large blue eyes.

Historical references to these people in the region around Rotorua & Taupo Lake districts:

‘Patu-paiarehe is the name applied by the Maoris to the mysterious forest dwelling race. An atmosphere of mysticism surrounds Maori references to these elusive tribes of the mountains and the bush....The Patu-paiarehe were for the most part of much lighter complexion than the Maoris...their hair was of a dull golden or reddish hue, “uru-kehu”, as is sometimes seen amongst the Maoris of today...This class of folk-tales no doubt originated in part in the actual existence of numerous tribes of aborigines. This immeasurably ancient light haired people left a strain of uru-kehu in most ancient tribes’ (see The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 1921, volume 30, pp. 96-102, 142-151, article by James Cowan).

Commenting on a later era, Cowan interviewed an old Maori elder who spoke of

the Patu-paiarehe of Mt. Ngongataha, Rotorua District. This partially wooded

area rising above the south-west shore of Lake Rotorua was the main regional

settlement of the Patu-paiarehe, whom the old elder called, Ngati-Hua (hua means

“bastard” in Maori). The old elder described the former residents

in the following way:

‘The complexion of most of them was kiri puwhero (reddish skin) and

their hair had a reddish or golden tinge we call uru-kehu. Some had black eyes,

some blue like Europeans. Some of their women were very beautiful, very fair

of complexion, with shining fair hair...’

Cowan was told by other Maori elders of the district that, many generations previously, the Maoris set fire to the fern and forest on the slopes of the mountain, causing much anguish to the Patu-paiarehe tribe and most of them departed northward.

It’s interesting to note that many very ornate little gable roofed, Saxon-style pataka buildings, a few of which are now preserved in the Auckland War Memorial Museum or at Te Papa Museum in Wellington, were seen abandoned and deteriorating on Mt. Ngongataha, by early colonial observers. These ornate structures were probably built for and by the very small white-pygmy people, as the doorways are tiny. Likewise, many gateways to villages had to be raised and widened in order to accommodate latter-era Maori occupiers.

J. M. McEwen researched one of these “Pakeha-Maori” tribes called

the Ngati-Hotu for over 15-years and used for reference the writings of Hawkes

Bay chiefs Raniera Te Ahiko and Paramena Te Naonao. Other researchers gleaned

information from genealogical tables related by tribes bordering Lake Taupo

and by interviews with the learned elders there. One quotation about the Ngati-Hotu,

derived from these Maori sources, states:

“Generally speaking, Ngati Hotu were of medium height and of light

colouring. In the majority of cases they had reddish hair. They were referred

to as urukehu. It is said that during the early stages of their occupation of

Taupo they did not practice tattooing as later generations did, and were spoken

of as te whanau a Rangi (the children of heaven) because of their fair skin.

There were two distinct types. One had reddish skin, a round face, small eyes

and thick protruding eyebrows. The other was the Turehu. They had white hair

and blue green eyes. They were fair-skinned, much smaller in stature, with larger

and very handsome features.” (see: Tuwharetoa, Chpt.

7, pg. 115, by Rev. John Grace).

‘It is most certain that the whites are the aborigines. Their colour is, generally speaking, like that of the people of Southern Europe and I saw several who had red hair. There were some who were as white as our sailors and we often saw on our ship a tall young man who by his colour and features might easily have passed for a European’ (see Voyages To Tasmania & New Zealand, by Lt. Croset)...The above observation was made in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand.

‘The Maori regales us with several tales that are supposed to illustrate a period when the Maori people were living here on sufferance, as it were, under the mana of the Turehu or Patu-paiarehe, the true lords of the soil. Many different names are used to denote this forest folk or fairies as our writers often term them, though the Maori concept is not that of a diminutive fey or elf like folk, but rather that of a people of ordinary stature and appearance, save they are said to have been fair-skinned and fair haired’ (see Maori Religion, by Elsdon Best).

‘Besides gods the natives believed in the existence of other beings,

who lived in communities, built pas, and were occupied with similar pursuits

to those of men. These were called Patu-paiarehe. Their chief residences were

on the tops of lofty hills, and they are said to have been the spiritual occupants

of the country prior to Maori, and to retire as they advance. The Wanganui natives

state, that when they first came to reside on the banks of the river, almost

all the chief heights were occupied by the Patu-paiarehe, who gradually abandoned

the river, and that even until a few generations ago, they had their favourite

haunts there. These may be accounts of an aboriginal race mixed with fable;

there are several things to warrant the idea that the Maori were not the first

inhabitants of the land.

The Patu-paiarehe were only seen early in the morning, and are represented as

being white, and clothed in white garments of the same form and texture of their

own; in fact, they may be called the children of the mist. They are supposed

to be of large size, and may be regarded as giants, although in some respects

they resemble our fairies. They are seldom seen alone, but generally in large

numbers; they are loud speakers and delight in playing the putorino (flute);

they are said to nurse their children in their arms, the same as Europeans and

not carry them in the Maori style, on the back or hip. Their faces are papatea,

not tattooed, and in this respect also, they resemble Europeans. They hold long

councils, and sing very loud; they often go and sit in cultivation’s,

which are completely filled with them, so as to be frequently mistaken for a

war party; but they never hurt the ground…

The belief in the Patu-paiarehe is very general; many have affirmed to me that

they have repeatedly met with them. Albinos are said to be their offspring,

and they are accused of frequently surprising women in the bush.’

(see Articles from “Te Ika A Maui, NZ and its Inhabitants”,

by Rev Richard Taylor, written in 1855; facsimile reprint in 1974 A.H. &

A.W. Reed).

Sadly, many hundreds of older New Zealand history books, written by on-the-spot

witnesses of significant events, or based upon extensive interviews with 19th

century & earlier Maori tohungas, etc., are now labelled “Eurocentric-

Ethnocentric” and conveniently discounted as unreliable without

any rational justification. In the past thirty years or so the dismal works

of approved-only, politically-aligned or politically-correct authors have supplanted

the comprehensive works of yesteryear. Much subject-matter related to our unravelling

New Zealand history or archaeology is now considered unmentionable and not for

general public consumption. Scholarship in fields of history, archaeology or

physical-anthropology has plummeted to being little more than thinly disguised

propaganda. Fortunately, there are still enough old-timers around who have not

succumbed to the enforced amnesia programmes that began to rear their ugly heads

by the mid-seventies. Many learned Maori elders know from their own oral-traditions

that modern selective, sanitised New Zealand history is, nowadays, severely

“truth-challenged”... (to use politically-correct terminology).

INTERNET REFERENCE TO BES.

...He was a grotesque-looking dwarf-god, but benign in nature. He was depicted wearing a plumed crown, normally with a beard, and his broad, mask-like face was surrounded by a lion's mane and ears. His tongue protrudes in a playfully aggressive manner. He looked like a bandy-legged dwarf dressed in either a panther skin or a kilt, and a lion's tail and he frequently carried musical instruments.

Protector

Together with Tawaret, his most important function was as protector of childbirth, and amulets of these two deities were immensely popular. His popularity covered common people´s homes as well as the royal court. Images of him have been found on walls at some workmen´s homes at Deir el-Medina, perhaps in rooms used for women and childbirth. He is also seen painted on a frieze on a wall in the palace of Amenhotep III at Malkata. There are decorations in the figure of Bes at everyday items like the footboard of beds and on the headrests, on mirror handles and on cosmetic tools and implements.

There is a spell which is to be recited four times over a clay dwarf which is placed on the crown of the head of a woman in labour, to help against complications. In it Bes is called: 'great dwarf with a large head and short thighs' and 'monkey in old age', here used as a means for defense against the dangers of childbirth.

Bes´ ugliness and aggressive appearance was, in typical Egyptian manner, used as a defense for the family and thought to ward off evil spirits and chase away serpents and scorpions from the house. He was often depicted as the demon Aha, strangling a snake in each hand.

Symbols

The 'Sa' hieroglyph, meaning protection, is often seen held by Bes, and he can also be shown with his arms outstretched and with hawk´s wings suspended from them. This conveys the solar symbolism of Heru of Behdety, not to link Bes with that particular god, but it was used for magical purposes.

Musician, merry-maker and bringer of good luck

Despite brandishing a sword and having a ferocious appearance, Bes has a genial temperament expressed through merrymaking and music. In the tomb of Queen Tiye´s parents, in Dyn 28, Bes is seen striking a tambourine, and more than 1000 years later, he still makes music, this time on a harp, in the temple of Het-Hert (Gr: Hathor) on the island of Philae.

Bes is first and foremost a deity connected with everyday life, but there are examples that he also appeared in some form in the Underworld. In the mythological papyri of Dirpu, the deceased comes to a gate guarded by a deity with the head of Anpu and the body of knife-wielding, serpent-strangling Bes.

The Late Period

He was also considered to bring good luck and prosperity to married couples and their children, and especially in the Late Period being connected to sexuality and childbirth. Therefore his image is found on all of the mammisi (birth houses) during this period, and his head is also seen above the Horus child on 'cippi' or stelae. It is also in this period that there were 'incubation' or Bes-chambers built at Saqqara. Their walls were lined with mud-plaster figures of Bes and a naked goddess, and it has been suggested that perhaps pilgrims rested there, hoping to have healing dreams for their sexual or fertile powers. In the Roman Period, Bes figurines exist where he is clad in legionary garb. His popularity went beyond the borders of Egypt, and his image is found at Kition in Cyprus, on an ivory plaque (ca 1200 bc.)and Phoenician ivory craftsmen decorated the caskets and furniture of Nimrod in Assyria... http://www.philae.nu/PerAnkh/perankhB.html

http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/bes.htm

To the left is seen front and rear pictures of an ancient Egyptian Bes figurine in green/ blue turquoise stone, presumably from a domestic household where children were present. To the right is the more popular and later form of the New Zealand greenstone Tiki. This perfectly cut and shaped "commercial" Tiki is the result of fabrication by diamond cutting tools, whereas the earlier, pre-colonial Tiki's, produced by the greenstone folk, were the product of many years of very hard labour. The earliest form of New Zealand Tiki had the somewhat more upright head, like the Egyptian exemplar of Bes, or the ancient Mexican equivalent to Bes/ Tiki.

The picture to the left is a Hei-Tiki found in Mexico. It is shown in volume XXXV of The Journal Of The Polynesian Society under the title, Notes and Queries (417) A Mexican Tiki. The Journal Of The Polynesian Society was, through much of the 19th century and throughout the 20th century, a very respected and prestigious scientific periodical. To the right is seen an Egyptian jade-nephrite (greenstone) neck pendant of Bes, which would have, undoubtedly, been worn by a woman, as Bes was the protector of pregnant women, mothers, children and the home. In New Zealand Maori customary practices the greenstone Tiki pendants were predominantly worn by women.

REFERENCES TO THE DWARF GOD IN ANCIENT MAORI NAMES.

In the ancient Maori genealogical (whakapapa) charts several of the ancestral lines preserve references to the dwarf God (Bes) in the names of ancestors. Maori personal names always described an event, object, emotional response or religious reference in the compound word that constituted the final rendition of the name. One of the ancestors was Po-maru-ehi, (also rendered Po-maru-wehi), which signifies (dwarf power of night). In the ancient tongue the terms "ehi" or "wehi" made reference to the dwarf. In the Maori language there is no "B" or "S" (no pun intended) and the natural way of rendering a name like Bes or Bessie would be something equivalent to Ehi or Wehi. Other names that appear to preserve some reference to the dwarf God are: Wehi-nui-a-mamao (great fear of the distant), Maru-wehi (power that trembles), Wehiwehi (dread), Taku-wehi (my fear), Po-maru-wehi (crushed by fear), Kahu-ngunu (garment of the dwarf), Haka-matua (dwarf parent), Rua-whewhe (pit of the dwarf), Maru-tauhea (tauwhea) (influence of the dwarf). Names like Rua-tipua (tupua) (pit of the goblin) or Whiro-tupua (goblin god) might also have once had reference to Bes/ Rongo. There are many names of ancestors that include Rongo and these seem to be based upon the South American route that the Bes traditions took in their migration to New Zealand. Perhaps there was a late mixing of the South American Rongorongo or Matuatonga potato God religious influences with the Egyptian dwarf God traditions. The dwarf God statuettes at portals or gates are often called Rongo.

Variations to these names, renditions or spelling related to the dwarf God, his attributes or possessions, are due to his having several names or that the above examples come from several different iwis (tribes) within New Zealand. In the earliest days there was no "singular" Maori language and although the spoken tongue seems to have been fairly consistent or understandable around the country, there were the usual and expected variations in pronunciation from region to region. Preserved, very ancient Waitaha language is purported to be a significant departure from modern Maori and quite guttural in its delivery. The Moriori language also had many significant, older language forms within it.

All of the primary elements are present, which demonstrate that the most common statues at Maori portals or village gateways are a regional expression of Bes, the dwarf God of Southern Egypt. The local version of Bes could not include certain of his faraway, Egyptian, protective cultural expressions, which related to the killing of threatening lions, snakes and scorpions, as all such species were unknown to or soon forgotten by the long-term populations of New Zealand.

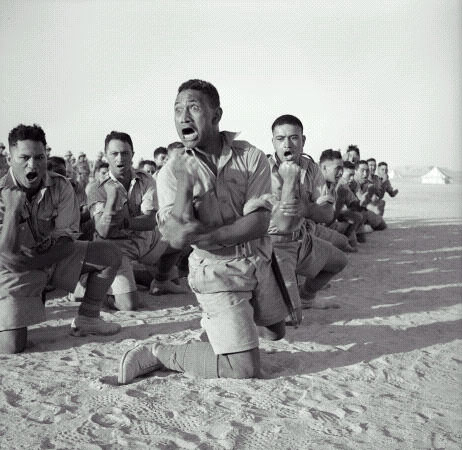

THE DANCE OF BES.

Masculine forms of the Maori haka were, without doubt, in the earlier era of the Patu-paiarehe people, dances of Bes, where the performer attempted to encapsulate all of the facial characteristics and physical attributes of the protective little dwarf god. The dancer, to this day, assumes a squat or bow-legged position and stomps the ground with all the force he can muster, slapping the thighs, rolling bulged out eyes, chanting ferociously while grimacing and poking-out the tongue. The fearsome display is designed to let any challenger know that there will be no quarter given and that unwarranted incursion will be met with ferocity unto death. This was the role of Bes, the unflinching, uncompromising protector of women and children. The male hakas of yesteryear, within living memory, were commenced low, at ground level, on one knee to accentuate the diminutive size of the dwarf god or to imitate his portrayed design on the Hei-Tiki pendant. In recent years the haka form that New Zealanders and the rest of the world have become most acquainted with is the one performed by the All Blacks football team.

Soldiers of the Maori Battalion perform a haka in the Middle East during WWII.

As in all haka performances, correct execution of the dance requires that the performer either squats low or assumes a position on one knee when commencing the dance. Throughout the haka the stooped or squatting appearance is religiously maintained. This can only be in homage to the diminutive stature of the ferocious little dwarf god Bes, down from whom the Maori haka dances of protection for the whanau have come.

When a dignitary goes, formally, onto a Maori marae they are accorded the honour of a challenge, wherein they are to walk unperturbed and without fear toward a weapon bearing warrior. The warrior seeks to intimidate the dignitary and break their resolve, courage and composure by threatening antics, movements, insane grimaces and active dance. The warrior assumes a low, squatting or springing position and bulges out the eyes in wild fury, the tongue darting and the face contorting to extremes. A token of peaceful intent is included in the ceremony, which allows the warrior to withdraw. The challenge contains all of the eye bulging, tongue lashing, symbolism of Bes, the dwarf god of Egypt, whose responsibility it was to vet all comers.

Despite the outwardly threatening appearance of the Bes haka dance to the uninitiated, women and children of the ancient tribes, or any who fully understood the benign tradition of Bes, would see a pseudo-serious/ comical aspect within the male haka and be both heartened and amused by it. Knowing that the dancer was imitating Bes, the audience would look to performers who excelled in providing the most pronounced impersonation.

The comical aspect of Bes-related dancing is, quite probably, preserved in

many of the haka dances of greater Polynesia. One of the most entertaining is

the Tahitian mosquito-dance, a very lively performance where the dancers jump

to and fro, slapping themselves mercilessly. In another memorable Tahitian dance

the belly is rolled in a very amusing way that’s guaranteed to bring the

house down with laughter. This hilarious ingredient of the dance, if it has

a pedigree back to the ancient Children of Poutini, would have been in homage

to the comically rotund, funny belly of Bes the comedian entertainer. It must

take the performers of this dance considerable practice to learn how to do the

bizarre tummy-roll. Belly-roll or women’s belly dancing has long since

been a traditional norm in Egypt and its satellite countries and is tolerated

by the Muslim religious leaders. The island of Moorea, opposite Papeete in the

Tahitian group, was called, ‘the island of the fairy folk with golden

hair’ (See: Riddle of the Pacific, by James Macmillan Brown).

It seems reasonable to assume that many of these dance influences were passed

down from the “Children of Poutini” ...the uru-kehu (reddish or

golden tinged hair) and kiri-puwhero (light complexioned, reddish skin) offspring

(fish) of Tangaroa/ Tangaloa who were, eventually, chased out of the islands

of Polynesia and fled to sanctuary in New Zealand. They were later found in

New Zealand by the newly arriving Polynesian/ Melanesians, who, for a time,

had to live ‘on sufferance ...under the mana of the Turehu or Patu-paiarehe’.

During this period of peace and sharing of unknown duration, the Patu-paiarehe

people taught many of their cultural expressions to Maori, including their Egyptian

forms of moko chin tattooing for women or the more extensive facial tattooing

for men. Maori oral traditions tell us that the art of moko was learned from

the Turehu, in such legends as the story of Mataora (Maori) and Niwareka (Turehu).

This account also speaks of the line or posture dances (haka) of the Turehu.

If Maori political activists, in collusion with PC-driven archaeologist/ historian/ anthropologist/ geneticist spin-doctors, continue to provide only limited scientific information that accentuates a solitary Taiwanese pedigree for Maori, then they dispossess Maori of their most profound cultural roots. European-Mediterranean civilisations have continuous used patterns like the koru, chevron and lozenge as their most venerated symbols, spanning millenniums. Some Maori stories-myths-traditions have very direct links to the ancient Greeks or Egyptians as the source of origin. The Hei-Tiki or Rongorongo, as well as potato gods and others, have obviously come via the South American route from the Mediterranean.

Language roots found in New Zealand pass back through regions like Peru (where about 10,000 well preserved Caucasoid-European mummies have been exhumed so far) to the Mediterranean. Significant numbers of Maori words are recognisable Numidian-Libyan, Hebrew or Indo-Aryan. Standing stone or mound-marker structures, decipherable measurement standards and cairn marked geometries across New Zealand are distinctly European-Mediterranean or have counterparts in those regions.

The same surveying-related expressions are found in the ahu platforms and moai statue layouts of Easter Island, where the cranio-facial form of the statues is dolicephalic, consistent with Caucasoid-European physiology. The statues were crowned with red top-knots to indicate the hair colour of the builders and don’t display the Polynesian rocker-jaw. These same geometries and measurement standards are duplicated throughout the ancient temple and city structures of Middle & South America, as well as within the multitude of geometric earth embankment complexes of North America. Maori pattern designs used in both tattooing or general carving show pedigrees back to groups like the Picts-Irish. The many laboriously hewn bullaun bowls, carved into solid rock, around New Zealand are yet another very significant cultural expression from ancient Ireland, etc., related to former Pagan ritual cleansing practices at the holy wells.

All over New Zealand there are ancient, carved bullaun bowls, just as one finds all over Ireland. Left: A perfectly preserved and unweathered South Auckland bullaun that was buried under ash from the 186 AD Taupo eruption, but exposed after road excavations in 1992. Next: A double set of bullauns in a trickle stream in Taranaki. Next: British Antiquarian Stuart Mason surveys a bullaun near Lyttelton, South Island, NZ, a well-known haunt of the ancient Patu-paiarehe. Right: One of two bullauns carved into white limestone above the beach at Mahia Peninsula. In Europe these hewn bowls developed into Roman Christian baptismal fonts, after the church fathers found they were unable to eradicate the ages-old ritual washing practices of the Pagans, so adopted them.

A Roman coin with Caesar Augustus stamped on it and dating to 7 BC was found

during excavations beside the Taylor River, Blenheim in December 2003. Another

was found many years ago in Hawkes Bay while a hole was being dug for a clothes-line

post at a new subdivision. With regards to similar finds in our region, a sculptured

stone Egyptian sacred scarab beetle from around 700 B.C. was found in the Hambledon

area of Australia. There was an old coin found

in the bottom of a hole being dug for a fence post in the mountains west of

Cairns in 1908, minted in the reign of Cleopatra's grandfather (Corliss, 1978:662).

Staple food plants or other useful plants of Polynesia, originating in Middle

& South America or Egypt and found in New Zealand, include: kumara, karaka

berry, the cotton plant, the bottle gourd, capsicum, banana, soapberry, tomato,

papaya, pawpaw, pineapple, manioc, maize, potato (many varieties), cabbage tree

(Yucca), the Nile Valley’s bulrush or catspaw as well as taro (several

varieties) from Egypt. Yam (a form of potato) could have come from various regions,

including Egypt and South America. The coconut, a major staple food found throughout

the Pacific, is not indigenous to the region, but was anciently introduced from,

seemingly, Costa Rica in Meso-America. The semi-flightless Pukeko bird of New

Zealand is widely distributed around the world from Egypt to Australia and one

is depicted climbing on papyrus stems in the Egyptian wall paintings at Medum.

Like the Kiore rat, the Pukeko (Purple Swamp Hen) is an anciently introduced

species. In New Zealand there are large old oak trees (indigenous to Europe

and the Mediterranean) that must have been planted well before British colonisation.

The early, traditional or religious dances brought to Oceania by the European/ Mediterranean people, thousands of years ago, would have included many dances of Bes for the entertainment/ protection of mothers and children. The haka is now, more-and-more, misinterpreted as solely an “offensive” warrior challenge, rather than a “defensive” protection dance. The loud and angry “war-dance” has become far too dominant in New Zealand society and has long-since pushed the more serene women’s long and short poi dances into the half-remembered background. Many New Zealanders don’t now know that the many other traditional dances even exist, as the emphasis by political activists for the past thirty years has been geared towards promoting very vocal Maori protest, amplified by the angry haka. Whatever happened to all the women’s graceful dances, with the easy listening harmonies, or the clever stick and hand clap dances of the children, (the dances of Niwareka)?

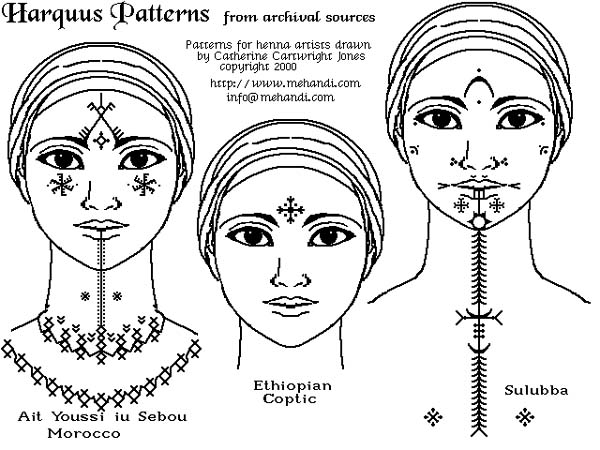

MOKO (TATTOOING)

This picture shows 3 Egyptian women (listed 1,2,3) with a Maori woman listed as (4). The Egyptian women are Assouan, from Upper Egypt. All display chin, lip or forehead tattoos. This picture and an accompanying article appeared in The Journal Of The Polynesian Society, Volume XIII - 1905.

The article and picture first appeared in the Otago Witness newspaper and included the following commentary, 'The London correspondent of The New Zealand Times says, - 'General Robley, the well known authority upon Maori art, sends me a sketch that he made of Assouan villagers now on view themselves at Earl's Court'.

'The sketch shows that the married women of this tribe far up the Nile are tattooed in a manner remarkably similar to that in which the Maori women used to be tattooed, namely on the lips and chin and now and again on the forehead.... General Robley has found on some of the earlier Egyptian mummies certain ornamental designs, which have hitherto been considered purely Egyptian, but he finds that they are identical to some of the most ancient Maori patterns' (emphasis added). See: The People Before, by Gary J Cook & Thomas J Brown pgs. 148, 150.

For further reference to traditional female facial tattooing (Harquus) of North Africa/ Egypt and it's Mediterranean environs see links extending from:

http://www.hennapage.com/henna/forum/messages/70857.html

On Tutankhamen’s death mask there is one extra forehead line on the left side. The forehead aspect of the moko on the young Maori chieftain, painted by Angus in 1847, shows an extra line on the right side. Both designs carry scientific information in the counts of dark and light lines.

On the Maori moko the count is 13 dark lines and 14 light lines, including the ornate centre band. The sum of 13 X 14 days = 182-days or the number of full days between equinoxes. Tutankhamen’s mask shows a cobra snake and ibis bird with a snake-like neck. The Maori moko centre band shows the Fleur de lys and Caduceus symbols, with the dual snakes entwined on the shaft. These are very ancient Mediterranean symbols, used copiously from Egypt to Ireland. The ancestors of the Turehu venerated the sun god RA and the spirals on each cheek represented the two solstice positions (Summer & Winter) with the nose-bridge position representing the equinoxes (Autumn & Vernal) in the endless journey of RA. Everything necessary would be present in the counts associated with this moko, if supported by some training in the wharewaananga, for the wearer to understand the full function of the Egyptian-Celtic, lunisolar Sabbatical Calendar.

The Maori word for “deformed” (haka) or “stunted” (hakahaka) applies equally to physical attributes of the dwarf god (Bes/ Rongo), as it does to the Bes-related dance (haka). Egyptian fertility/ good-luck tattooing is called Harquus. The tattooing or body painting, ritually done in ancient Egypt, was also strongly associated with dance. In Egypt, a female version of Bes existed and this appears to have been case in New Zealand also.

Traditional Bes-related belly-dancing for fertility/ good fortune/ protection, as found in Egypt, also uses facial tattooing (harquus). In addition, there is the more extensive body tattooing or painting (henna), which is comparable to Pacific patterns found on sacred tapa cloths (painted prayers or rangoli). Some groups never made permanent, scarring tattoos into their skin, but only painted the face and body on special occasions (like the Picts, with their warpaint of blue woad, which made them look fearsome when doing battle against the hated Romans).

THE DEMISE OF THE PATU-PAI-AREHE (EUROPEANS).

In the later carnage, the villages of the Patu-paiarehe and all possessions not hidden in swamps or secreted away in the ground were taken over by the warriors and the former people annihilated or forcibly enslaved. The earliest greenstone Hei-Tiki pendants (Bes) and greenstone patu/ mere’s (SA hieroglyph ceremonial protection symbols) were taken as prizes of conquest from the Children of Poutini, also known as the greenstone folk and the white, flaxen haired offspring of Tangaroa, god of the Sea. The primary gods of these Patu-paiarehe or stonebuilders were, Ammon-RA in squatting form (well-preserved in Moriori culture), Taranicus or Taranaich (Taranaki)...Celtic god of thunder and lightning and Bes/ Puck the dancer/ protector of the home. The Egyptian supreme god RA (the Sun), in conjunction with and embracing Nut (wife of the Sun-god) seems to be depicted by Rangi (also known as RA) & Papa in New Zealand. There were also bird headed gods, which seemed to come to New Zealand (via Easter Island) from South America and aquatic, serpent-headed or dragon-headed gods, which might have come from regions like Scandinavia.

The picture to the left is the supreme God, Ammon RA, shown on the Egyptian Hypocephalus funerary amulet. This is the ribbed, squatting god, which is a derivation or metamorphised rendition from early astronomical geometry of Egypt. The three figures to the right, showing the ribbed, squatting God, are Moriori from the Chatham Islands of New Zealand. In the Egyptian example the 4 rams heads of Ammon-RA look to the 4 quarters of the Earth and above the heads sits the plumed crown of Ammon RA. In the 3 Moriori examples to the right of the Hypocephalus, an artistic attempt, thousands of years removed from the Hypocephalus amulet depiction, very adequately preserves the sideways looking faces and overhead crown of Ammon RA the Sun God (see the middle one of the 3). The extreme right hand rendition is a tree trunk carving and the "V" returning (chevron) placement of the arms attempts to duplicate the balancing staffs on the knees of Ammon-RA. It is a tremendous accomplishment of the Moriori Tohungas and learned Kaumatuas/ Kuias to have preserved this symbolism, in distant isolation from the mother country of Egypt, so well for so long. The Chehalis (Coast Salish) Indians of North America preserved the symbolism in almost duplicate manner.

THOR IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC

Mount Taranaki was, without doubt, ancient New Zealand's foremost navigational beacon. As an active volcano on the western sea coastline facing Australia and Western Polynesia, it's smoky plume would have been visible for a great distance over the horizon. In line with similar belief systems amongst great civilisations, its imposing majesty would have invited religious veneration, in conjunction with the other volcanic peaks further inland. "Tara" in Maori means apex, fin or spine.

The very ancient European tribes migrating all the way to Britain left a trail behind them of "Tara" derived names

In consideration of ancient Welsh/ Gaelic/ Breton/ Khumri variations on "Tara" we have the following:

"Taran" means "thunder"

in Welsh/ Breton/ Khumri. The word "Tardd" would mean

"breaking out".

"Tartar" means noise

or clamour in Irish/ Gaelic.

Each of these descriptions in Welsh/

Khumri or Irish/ Gaelic migrated to Wales and Ireland via Scandinavia and Germany,

where "Thor", meaning literally"thunder", was

the pre-eminent Deity and created great thunder claps by crashing two rams heads

together.

The Continental European Celts called their God, "Taranis"

(the thunderer) and he bore that name in France and Spain amongst the Druids,

as well as, seemingly, Celtic countries like Germany, Switzerland and Yugoslavia

further east. The name Taranis derives from the Celtic (or Indo-European)

root "Taran" meaning "thunderer or thunder" and he

was associated with Jupiter.

Another variation on the name was

"Taranucnus" or "Taranus"...used in Britain. Taranaich

(which is very close in pronunciation to Taranaki) is the Scot/ Pict/ Gaelic

god of thunder & lightning. His name was derived from the Gaelic word tarnach

or tarna, ‘thunder’. His attribute was the spoked wheel.

Taranis, Taran, Taranus, Taranucus, Taranucnus, Taranaich all relate to

"Thunderer", the Celtic thunder god and ‘god of heaven’.

His symbol was the spoked wheel and a stylized spiral representing lightning.

The wheel was normally considered to be a sun symbol, but could also be associated

with the thunder god's chariot rumbling across the sky.

The Celtic tribes, Turones, Turoni, Taurini, venerated the

deity Taranucus/ Taranaich, which is not a tremendous departure from saying

that the Turehu of ancient New Zealand lived in the foothills of Mt, Taranaki.

A pre-Maori white tribe was called the Turehu.

The

Maori name for the God of thunder and lightning is Tawhaki, which might

explain how the second half of "Taran-aki" (aki) became

predominant in the finalised nomenclature that described this God regionally..

According to the Roman poet Lucan, Taranis was appeased by burning (Bellum civile or Pharsalia I, 422-465).

This way of describing Mount Taranaki's name, which is the result of a more direct route of migration and influx of European cultural idiosyncrasies from Britain and Continental Europe to New Zealand, is very apt. It describes a thunder and lightning god (inseparable elements) that is appeased by fire. Again the god is associated with one of the great lights in the firmament (Jupiter). This name (Taranis/ Taranucus/ Taranaich) and description of the god's attributes fit the profile of "an active "VOLCANO".

The early beliefs of the Aryans, who migrated west into Europe, were retained in various regions of India and the Hindu God Indra is Taranis/ Taranaich.

The name "Taranaki" is found in the Waitakere Ranges of Northern New Zealand. Also, Wellington Harbour adjacent to New Zealand's capital city used to be called "Tara" as the Maori placename for the area. The ancient name "Tara" is used prolifically all over Ireland in many placenames.

In correspondence with a lady in Britain , I was told that in the Welsh language the term for "royal dog" is rendered "Cu-ri", whereas in the Maori language it is "Kuri", a parallel that my correspondent found "Cu-ri-ous". She also pointed out that the ancient Welsh called themselves "Cu-m-ri".

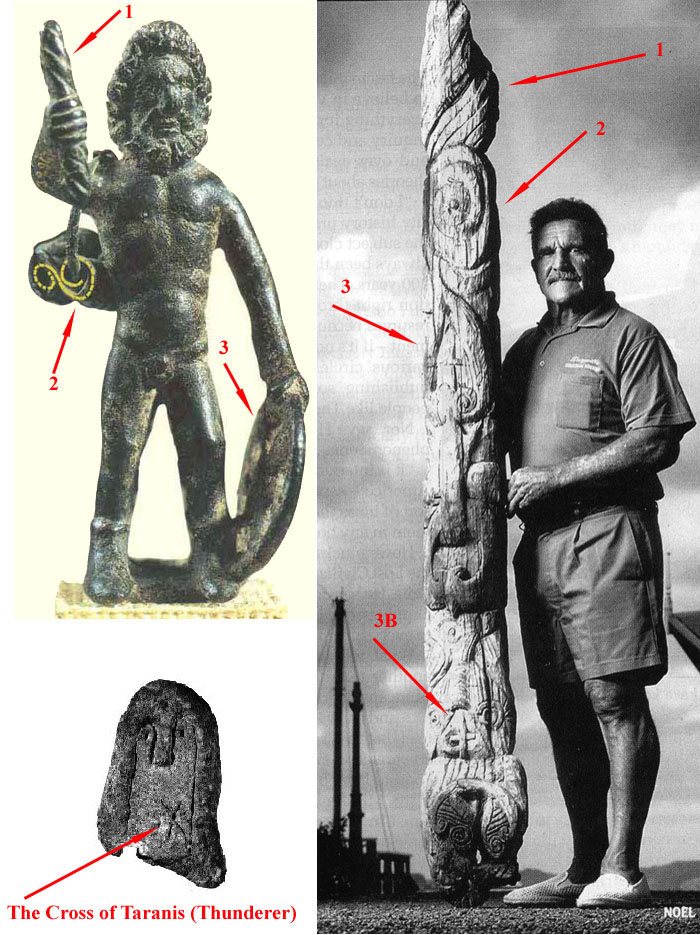

TARANAKI/ TARANAICH

In the picture to the upper left is shown a statuette, found in France, which depicts the ancient god Taranis and his identifying elements. These are:

In the picture to the lower left is shown a "cross", known as the "Cross of Taranis" (Croix de Taranis). In pre-Christian France (Gaul) the spoked "thunder wheel" of Taranis was often represented as a "cross".

In the picture to the right is shown Curator of the Dargaville Maritime Museum, Noel Hilliam, holding an ancient totem (Nui pole), which was retrieved from wetlands in the north of New Zealand. The totem has, carved into it, all of the elements associated with Taranis, the Thunderer. These are:

The Celtic god Taranucus/ Taranaich is associated with the measurement of time and has at his side the “Wheel of the Seasons”. This is a multi-spoke wheel that is very comparable, in style, to the North American Indian stone “Medicine Wheels”, which were astronomical observatories laid out on the terrain. Thus far, about 80 such stone Medicine Wheels have been identified in North America.

It’s significant that ancient Celtic coins of Britain invariably showed spoke wheels as a main design feature.

Our New Zealand standing stone observatories are, essentially, like spoke wheels in many cases, wherein there is a central hubstone and lines of stone (or alignments marked by stone) that extend outwards in coded lengths and angles to the outer-marker stone. At Koru PA, in full view of Mt Taranaki, is a sophisticated standing stone circle, which also includes a multi-component overland alignment marching towards Mt. Taranaki’s highest pinnacle peak.

On the carving held by Noel Hilliam are at least two sections that show crosses,

which would symbolise the spokes of the Wheel of the Seasons associated with

Taranucus/ Taranaich. In the Auckland War Memorial Museum are ancient Maori

canoe prows, some of which feature the solar wheels of Taranis/ Taranaich.

Representations of the Roman god Jupiter (Taranaich) include solar wheels, as found on the above prow.

The largest wheel on the canoe prow indicates the primary and secondary points of the compass. The four, six or eight spoke designs are also seen on old Celtic coins. The second (central) design has a dual function, wherein it is (a) a cross pointing to the 4 quarters of the Earth (including equinox rise and set positions) and (b) a caricature of the squatting god Ammon RA of the Egyptian Hypocephalus.

The third solar wheel shown (six spokes) fixes onto the rise and set positions of the Summer and Winter Solstices (about a 60-degree spread for the latitude of New Zealand’s North Island). The Solar Wheel beside the French statuette-artefact of Taranis/ Taranaich also has six spokes.

The origins of this canoe prow are not known fully to this researcher. It might have been newly carved as a gift from the Maori people to Governor Sir George Grey. The inclusion of these “Jupiter Solar Wheels”, should have been based upon traditional-religious carving styles and patterns, from which Maori of that era did not deviate. (Compare: The Britannia shield also).

PATU-PAIAREHE

Scholars probing definitions and development of the Maori term "Pakeha" (Maori name for white people) state the following:

The most likely derivation seems to be from ‘Pakepakeha’ (George, 1999) mythical creatures who are mischievous, human-like beings, with fair skin and hair who lived deep in the forest, coming out only at night. (Biggs, 1988).

The ‘Pakepakeha’ are also linked to ‘Patupaiarehe’ by their fair skin and hair. The ‘Patupaiarehe’ had fair skin and beautiful voices, and gave people the secret of fishing with nets. These creatures’ possess canoes made of reeds, which can change magically into sailing vessels. The ‘Patupaiarehe’ can also be linked to Nahe’s version of Pakeha as an abbreviation of ‘Paakehakeha’, gods of the ocean who had the forms of fish and man (Biggs, 1988). See: http://maorinews.com/writings/papers/other/pakeha.htm

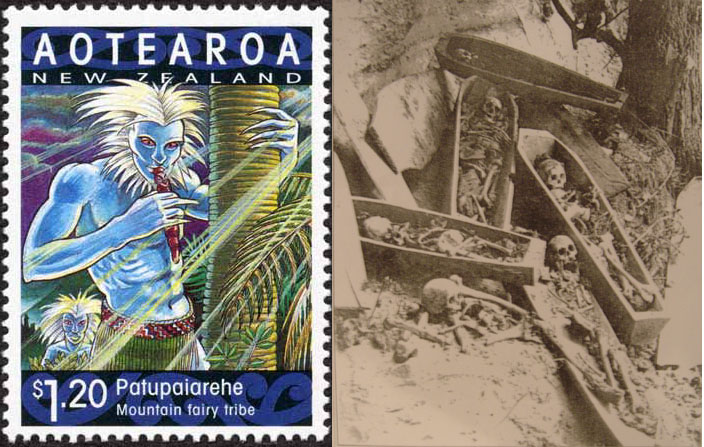

A New Zealand stamp attempts to portray, in surrealist imagery, the pre-Maori Patu-paiarehe people, now all-too-conveniently relegated to the realm of myth and legend.

Large pockets of the pre-Maori European tribes, who were the long-term inhabitants of New Zealand, still survived into early colonial times and the first colonial accounts called them the Pakeha Maoris (white skinned Maoris) who lived inland. The Patu-paiarehe individual shown on the stamp plays a carved putorino flute and wears a piupiu skirt, or kilt adorned with the very Celtic or Pictish-looking design-work that parallels the design-work now found in Maori culture. All or most aspects of Maori culture, including associated symbolism and taonga (treasures), were taken from the Patu-paiarehe, as the spoils of war or conquest (muru-plunder). It is now considered to be Maori in design origin, but is, in fact, ancient European, with a pedigree back to the Mediterranean.

After the coming of the Polynesian-Melanesian cannibals to New Zealand, the

earlier people were hunted to extinction as a food source. Many of the Patu-paiarehe

or Turehu women were forcibly absorbed into the Maori tribes as slaves. Fugitives

or survivors amongst the earlier people moved to the very rugged and remote

interior of the country and lived in the deep forests or dark caves, many succumbing

to lung ailments from constant hiding out by day and foraging by night.

Photo courtesy of Rob Graham - Wanganui Photo News.

The coffins seen above were photographed in 1919 high up a cliff-face at a very remote part of New Zealand. Each coffin was hewn-out by stone tools from a single log, like a dugout canoe (photo: courtesy of Rob Graham).

These coffins were not planked or made from sawn timbers, as one would expect

colonial-European coffins to be fabricated at any point during the colonial

era. The lids were also hewn from a single, thick plank, with the edge lip (used

for locking the lid firmly onto the coffin box) laboriously carved by scalloping

out the central region. The cultural habit of carving coffins in this manner,

as single hewn pieces, is reminiscent of the mummy-boards of Egypt, which fully

encased the body of the deceased. One skeleton lies on what appears to have

been the base of an old canoe.

These skeletons display recognisable European physiology. They were already

very old when found in isolated country, far from the consecrated ground of

a churchyard. The deceased people were, undoubtedly, the white Ngati Hotu, known

in local Maori and European folklore to have hidden from the cannibals for centuries

in this inhospitable region. The location was less than 50-miles further into

the rugged badlands interior from where the last of the Ngati Hotu tribe were

defeated and cannibalised in the “Battle of the Five Forts” at Pukekaikiore

(hill of the meal of rats).

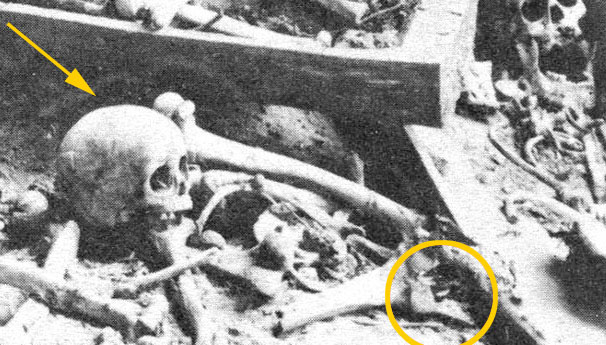

A blow-up of the picture positively shows a side view of a jaw (mandible)

adjacent to the canoe base, which is not the Maori-Polynesian rocker jaw with

a continuous downwards curve on the lower border. Further to that, the eye sockets

of these people are squarish, the nose openings pyramidal, the faces long and

narrow (dolicephalic skull type) and the craniums very round. The face line

from the jaw past the nose and brow is consistent with the European facial profile,

rather than the very flat face of the Maori.

The craniological features and general visual evidence shows that these very round skulls are not Polynesian, but are consistent with European physiology. The yellow circle shows a mandible that is not the Polynesian “Rocker Jaw”.

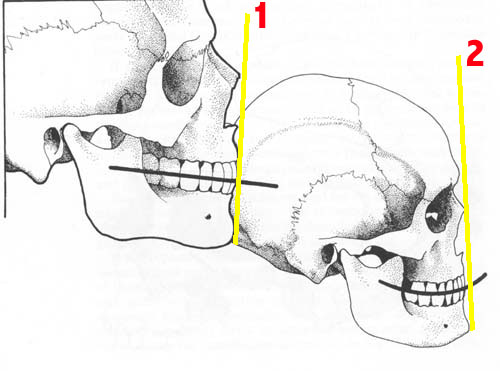

Phillip Houghton, in his book, The First New Zealanders, 1980, offers

comparisons between the Maori-Polynesian physiology and that of other racial

groups (yellow lines & numbers added).

The cranial image to the left is typically European, showing the face line,

straight set of the teeth and upward indented (concave) mandible. The skull

to the right is Polynesian Maori, which varies markedly from these features,

including the very distinctive rocker jaw and general shape of the cranium.

For anyone seeking a comprehensive description of skeletal differences, Houghton’s

book is a valuable resource.

Houghton writes:

'When the Polynesian skull is placed beside that of a European,

or any other race, differences can be seen. The Polynesian head, particularly

of the male, is more angular, appearing distinctly pentagonal from above or

behind, compared with the rounder contour of the European. The region of the

temples is particularly flat in the Polynesian, and the bridges of bone known

as the zygomatic arches stand well clear of the crainial contour, being visible

from above. In the heads of most races these arches are usually concealed by

the cranial contour in this view.

Viewed from the front the face appears flat-sided with the cheekbone turning

back at right angles to the facial surface. Viewed from the side the face of

the Polynesian appears flat, vertical in profile, and not usually with any projection

of the front teeth and their supporting bone as commonly seen in Negroes, in

whom also the point of the chin may be set back so that the whole of the mid-face

appears to project forward. The vault of the Polynesian cranium is high. And

from the side view is seen what is probably the most distinctive Polynesian

feature of all, the shape of the mandible. The lower border of this bone shows

a continuous and marked convex curve from front to back This means that when

the isolated bone is placed on a flat surface it makes contact at only two points,

and therefore rocks when disturbed. This has given rise to the term familiar

to Oceanic anthropologists as describing the Polynesian mandible - the rocker

jaw.' (See The First New Zealanders, pp. 41-44, with illustrations).

In 2004, Member of Parliament, the Hon. Chris Carter, was asked, under an “official information” request, how many archaeological “embargoes” were presently in place. He forwarded a written response that there were 105 current embargoes, mostly concerning burial sites. It was stated that “DOC administers the New Zealand Archaeological Associations Central file ...of which, 105 ... were classified as sensitive records”. The response stated: “File keepers may create sensitive files ....if this is requested by the site recorder...”

One of these embargos of recent years included a 75-year suppression of information

related to a cache of large stature skeletons at Waikaretu, 12-miles SSE of

Port Waikato. The very tall people (measured to be 7-feet or more) were laid

out on cut shelves in a cavern, which was exposed during road widening excavations.

Anthropologists from Auckland and Waikato Universities were called in and, to

the dismay and disgust of the roading contractors, they slapped a moratorium

over the find, requiring that it be kept secret from the New Zealand public.

Maurice Tyson of Tuakau, a contractor in the area for 50 years, recalls how

this upset the men who had discovered the cave. They could not understand why

such a valuable, history-changing, archaeological site should be kept secret.

In 1988, archaeologist, Michael Taylor slapped an embargo on any release of

information concerning the ancient, stacked stone structures in the Waipoua

Forest, but that embargo was partially broken by a private citizen’s legal

challenge after 8-years.

What this means is that the “powers that be” assume the authority

to veto any mention or release of information they consider not suitable for

the public. The reality is, however, that all skeletal remains of the pre-Maori

people, when located in caves, rock shelters, sand dunes, etc., by hunters or

others and reported to the authorities, are inevitably buried, removed or destroyed

by concealment teams associated with the local iwi or Department of Conservation.

Since the beginning of New Zealand’s colonial era, innumerable anomalous

skeletons have been seen in dry burial caves and some of these were in coffins

or more-often laid out on stone shelves, etc. On rare occasions, some bodies

have been seen to be encased within solidified tree gum. Many skeletons have

been observed to have the blond, red or brown hair hues, typical of Europeans,

and are often accompanied by carved greenstone or other kinds of funerary objects.

In coastal sand dunes, as elsewhere, the skeletons are mostly found to be buried

in a foetal or sitting position, with the knees drawn up to the chest and trussed

(tied). This is similar to Beaker-People burials of ancient Britain or the innumerable

mummy-bag burials of Peru.

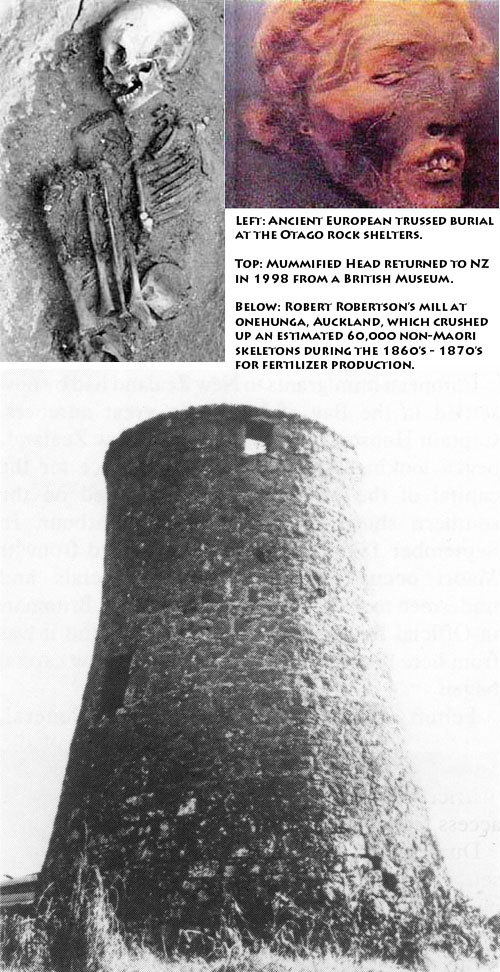

For about 12-years during the mid 1860’s-70’s Robertson’s Mill in Onehunga, Auckland ground up tens of thousands of Patu-paiarehe skeletons from the Auckland and Northland burial caves to make fertiliser. Maori leaders had told Governor Bowen at Te Kopuru in 1869, ‘Do with them what you wish for these are not our people’ (Source: Noel Hilliam, former Curator of the Dargaville Maritime Museum).

This statement to Governor Bowen parallels what historian/ anthropologist Edward

Tregear heard and wrote:

“The Maoris used to pay great respect to the bones of their dead,

yet here and there may be found among sandhills, etc., human remains uncovered

by the wind, and of these no tradition remains, as there would certainly be

if the relics were those of ancestors. The natives say, “These are the

bones of strangers.” So also mortuary-caves are found concerning the contents

of which the Maoris make the same remark, and regard them with indifference”

(See: The Maori Race, pp. 562-563).

‘Eden Mill was at this time operating as a bone mill used to grind the bones into fertiliser. It was owned by one Robert Robertson whose impious enterprise made use of the Maori dead found in enormous numbers in caves and caverns in the district’ (see: The Changing Face of Mt. Eden, 1989).

Of course, Maori would never condone any disturbance of the remains of their own ancestors, but these were “strangers” who had died long before Maori arrived on New Zealand’s shores.

A few years ago a Northland, researcher, Shaun Reilly, raised a lot of this

evidence about pre-Maori settlement before the Northland Conservation Board

(Department of Conservation). In a newspaper article by journalist Leighton

Keith it was reported that, ‘Northland Conservation Board Chairman,

Lew Ritchie said most board members were aware this evidence existed, but the

board was too busy to investigate further’.

Yet another cache of cannibal victim bones, such as one finds all over New Zealand.

No scientific investigation of racial characteristics of any such remains is permitted. The chronic suppression problem is very general throughout the Pacific. Dr. Lisa Maltisso-Smith admitted in a NZ Herald Newspaper interview in 2004 that: ‘Ancient human remains in the Pacific are rare and off-limits for study. So there was no hope of comparing genetic variations in old and new human tissue’.

Self-portraits on the pottery of the Pacific’s ancient Lapita People show long-faced dolicephalic cranial indexes, with the narrow beaked leptorrhine nose, wide eyes, thin lips, wavy flowing hair and moustaches, consistent with European physiology.

One Maori oral tradition says that the "greenstone folk" [the people who carved greenstone] were the "Children of Poutini", who were also the offspring of Tangaroa. He was the god of ocean migrations and all fish and the "Children of Poutini" were the fish of Tangaroa. To get greenstone treasures one had to catch the fish of Tangaroa, put them in the oven and take their greenstone.

YET ANOTHER CACHE OF PRE-MAORI SKELETONS DESTROYED BEFORE THEY CAN BE STUDIED.

Old Maori skeletons get new home

24

September 2005

By RICHARD WOOD

The remains of 12 skeletons in a formal pre-European Maori urupa (cemetery) unearthed by contractors on a Manutahi farm, have been removed and re-interred at Manutahi Marae by kaumatua of the Ngati Pakakohe iwi.

No official comment could be obtained from Pakakohe, but tribal members told the

Taranaki Daily News the blessing and reinterrment happened on Tuesday.

These sources were not comfortable with the removal of the bones.

They said the remains should possibly have been left where they were found.

The principal South Taranaki iwi, Ngati Ruanui, was originally called in by the police after the remains were disturbed during land contouring earthworks for oil exploration company Swift Energy NZ Ltd, on September 13.

Ngati Ruanui chairman Syd Kahu, asked for an update this week, said: "I have handed it all over to Pakakohe, that's all I have to say."

Allan Cunningham, the new Swift CEO said nothing further was being done at the site "until Ngati Ruanui decide to allow it. They may do as they see fit, that's our position. There has been a limited amount of fill work done where the remains were found."

Michael Taylor, a private archaeologist from Archaeology North, Wanganui, was called in by the NZ Historic Places Trust to assess the discovery but did no excavation.

He said the urupa "definitely pre-dates European settlement due to the style of burial, state of the bones and the presence of what may have been woven flax. Something like this is a significant discovery because it is an unrecorded formal burial site. I've been in archaeology for over 20 years and this is the first time I have seen anything like this."

Since the find, a bit more evidence has filtered through from private sources. This tells us:

The remains, which were undoubtedly pre-Maori or of ancient Patu-paiarehe-European ethnicity have, as per usual, been whisked away and destroyed, this time at Manutahi PA located between Hawera and Patea. This "Dark Ages" practice of suppressing scientific investigation ensures that we never learn the truth about our long-term history of New Zealand. Moreover, the progeny of those who annihilated the earlier inhabitants of New Zealand are aided and abetted by the authorities in keeping knowledge concerning the earliest New Zealanders a deep, dark secret.

Europeans have a right to be consulted regarding the fate of the remains of their ancient cousin peoples. This is yet another breach of, what should be, mutual respect for ethnic rights.

SO, WELCOME TO THE "DARK AGES".

It has been correctly stated by one observer: 'it's virtually all corporate science now' and information is carefully vetted, seived and sanitised by social engineers before it's deemed suitable for presentation to the masses. Such is the reason behind the destruction, instead of forensic analysis, of ages-old skeletal remains from a Taranaki swamp.